mensanthropist [ men-san-thruh-pist ] noun

a person, who actively participates in fulfilling one of Mensa’s objectives by fostering and utilizing intelligence for the benefit of humanity

In this episode I bring you an interview with Jakub Nešetřil, founder of Česko.Digital. Jakub and I have known each other for more than 25 years since we founded Klub přátel počítačů Macintosh („The Macintosh Friends Club“), which was informally known as the Apple Club. Jakub graduated from university, went to New Zealand for a while, where he worked as a backend programmer, met his wife there, and after returning to the Czech Republic, he spent some time programming frontends at GoodData, until he was approached by a lecture by Ryan Dahl from JSCONF in Berlin and went to a javascript hackathon.

Jakub won the hackathon with his tool for designing, testing and documenting APIs (application programming interfaces used for communication between applications and between application components – e.g. between frontend and backend). This then became the product of a new startup called Apiary. After successfully growing the company in Silicon Valley, Jakub sold it to the American giant Oracle.

Part of the company acquisition contract was Jakub’s condition that he could return from Silicon Valley to the Czech Republic. Here he worked for Oracle for a while, but then decided to make his family and health a priority and left the company. That didn’t last long however, and two years ago he started another project, which has somehow managed to touch most of us since then…

Jakub, do you call it „Česko dig-it-ahl“ (Czech pronunciation) or „Česko digital“ (English pronunciation)?

I call it „Česko dig-it-ahl“. Originally it was going to be called Code4Czech Republic because there is a worldwide network of similar organizations. It started as Code4America and there are others around us, Code4Netherlands, Code4Germany, Code4Poland, Code4Romania. Then it almost all fell apart when we argued about whether it should be Code4Czech Republic or Code4Czechia, until someone pointed out that it should be primarily for Czechs, so let’s have a Czech name. So I named it Česko (Czechia) dot Digital. Partly because the domain cesko.digital was available. We even have the diacritical version česko.digital. 🙂

Did you first find out that these organizations existed, or did your idea to do some charity thing come first?

The idea gradually developed from both sides. The first germ was probably my experience in Silicon Valley. Mainly from Code4America, where I knew some friends, and also from being there during the Barack Obama era. He put together a very tech-heavy group of people to help him with his digital campaign. It’s sometimes being said (and it’s a bit of a cliché, but true) that when you come back from Silicon Valley, what you bring with you is this feeling that technology is changing the world.

The second impulse was when I came back to Czechia and said to myself that very carefully and sparingly I should start getting a little bit into philanthropy and giving something back to society. Even from what I made in Apiary, because, and this seems to me completely inhumane to this day, profits from shares you hold for more than three years are not taxed in Czechia. So I thought I need to tax myself voluntarily.

I started looking for where to send some of what I earned, and I experienced the biggest kind of „analysis paralysis“ of how to evaluate all these non-profits and charities based on their efficiency. Once I brought that business mindset, I immediately wanted to look at „return on investment“, or how much good one dollar or one crown buys me, but I found that very hard to compare.

Then I got the idea to look at how those organizations use technology, because I understood that. I thought that if I see someone using technology well, there’s probably a good chance that they’re managing their organization well. So I started looking for charities that used technology well, but I didn’t find any either.

When I saw how the non-profit sector and the whole public space, not just non-profits, but also contributory organizations, schools, hospitals, and then of course up to the government, how technologically outdated all that is, and on top of that you see that the Czech Republic is horribly out of touch in the commercial sector, we have a lot of strong technological companies here, a lot of qualified people, even across the board the society is very tech-savvy, for example we are also the first in Europe in the use of contactless payment cards, I started to think that something needs to be done about it. So I founded Česko.Digital.

What did it take to get it going?

I was very lucky to come across the OSF Foundation, which was working on a similar topic, digital civil society, and they gave me some direction. I started doing market research abroad, talking a lot with Germans, Romanians, Poles. Then I started releasing sort of trial balloons here in Czechia. At several programming conferences I gave a lecture that programmers should also feel social responsibility and try to help move society for the better, and it always had a great response. Everyone just asked what they should do then.

So two years ago we started a non-profit organization. Of course, it turned out to be much more complicated than we naively imagined. It’s not enough to find tech-savvy volunteers and say, „we have a lot of programmers, tell us what you’d like,“ because everyone says they want a new website. Or at best, they want a mobile app. Because that’s all they know about the technology. Whether the app will be useful or whether it will actually help, that’s beyond what they ask about.

So it’s not like throwing this supply of lots of tech-savvy people into the market and working on what organisations ask us. We need to help them think a little bit digitally. So it’s partly become an innovation agency, a kind of incubator, helping organisations who apply. Our job is to figure out where their current problem is and how technology could help them with that problem, and then finally implement the solution.

The technical implementation is the main thing everyone is waiting for, but they no longer see what needs to precede. The other day, some deputy in the Ministry of Education told me: „Well, that’s not going to work, because it would require deployment of artificial intelligence.“ And I laughed and said that if the only problem we had was artificial intelligence, then it could be solved right away. There are lots of volunteers at Česko.Digital who are looking forward to getting their hands on some AI.

And now, two years after our founding, we are the largest „civic tech“ organization in Europe with more than four thousand registered volunteers.

How do you come up with projects, do you think of whom to help, or do you just wait for a non-profit to ask for your help?

It doesn’t have to be a non-profit, the main criterion is that Česko.Digital works pro bono. Always. So volunteers don’t get paid for it, but at the same time the organization we work with doesn’t pay anything either. That’s why, by definition, we can’t work on commercial projects. Even if it’s a publicly useful commercial project, it’s hard to have volunteers working there for free and then someone making a lot of money off of it. But in addition to NGOs, we also work at the level of cities, municipalities and regions, at the level of contributory organizations such as hospitals or schools, and then of course with the state administration. And some of the projects intersect with all of that.

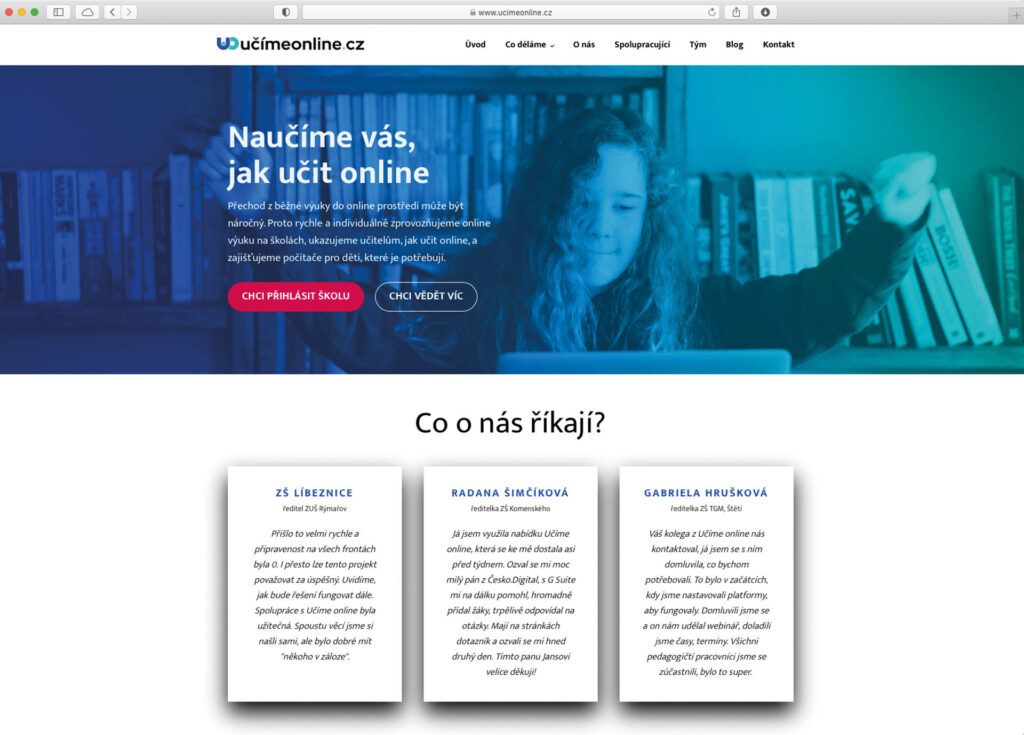

For example, Učíme online („we teach online“) started as our own idea. But when an idea arises internally, we try to find a partner for it who has that domain expertise as soon as possible. Because Česko.Digital is not an expert in education, in mental health, in social policy, or in health care. We always need to find an organisation that has the know-how, has a vision and owns the project, and then we help with the technology part.

But a very large part of those projects come from the outside. We have a process for that and we try to sort those projects and pick the useful ones. The way we see it is that the volunteers who work at Česko.Digital get the service from us of finding projects that are meaningful and sustainable. It’s not like I’m going to work on something here for six months and then they throw it away because they got it for free.

Is Česko.Digital entirely made up of volunteers, or does it have some administrative apparatus and staff you need to find funds for somewhere?

It does, and it’s not even a small organization anymore. We looked at what such organizations look like abroad. For example, the one in Romania that I used as an example had 20 full-time employees for 1,000 volunteers. We have around 15 people. Which is severely undersized for 4,000 volunteers compared to the Romanians or the Dutch, but again, it’s only a two-year-old organization. The job of these people is not to do the work for the volunteers, but to provide the infrastructure and services to the community to make the volunteers work efficiently. These people cover those projects and provide long-term continuity. This is important because it’s natural that volunteers come and go. There’s a much higher turnover of people who are rotating on those projects, and there needs to be someone there to cover that.

Initially I paid the costs, but that can’t be sustained in a long term. This year should be the first when Česko.Digital manages to find the funds to run itself. I wanted to build it in a similar way to a startup, doing some work at the beginning, showing what such an organization is good for, and thus earning the privilege to talk to our partners about why they should support Česko.Digital.

My big goal is to make Česko.Digital independent of foundation funding, because we are here to help the non-profit sector, not to suck more resources away. We are looking for partners among Czech technology companies that are looking for a role in Czech society, companies like Avast, Seznam or Google, or even Škoda or Česká spořitelna. Organisations that are such digital pioneers in their respective fields. Partners who cooperate with us not only financially, but also by having their employees work and use their experience in Česko.Digital during their volunteering days.

The whole idea of Česko.Digital is based on the fact that if a person wants to help the society, they should not stand by the underground and sell yellow chickens, because that absolutely does not respect their value, experience and knowledge. If someone works as a top project manager because they know how to coordinate people and manage projects, it doesn’t make sense for them to help the society by picking up trash with GreenPeace. But there were no well prepared ready-made projects where an experienced project manager could come in and say, „I’ll be happy to manage this now in my spare time and help out with something.“ Somebody had to do a little bit of preparation first.

I know it’s hard to do this fairly, but could you pick out three projects of yours that people might be aware of but might not know that Česko.Digital is behind them?

Probably the biggest project in terms of scope and effort was Teach Online. A lot of people may not know that we have trained thousands of teachers, about 700 schools and distributed thousands of computers and tablets to families who didn’t have computers at home. We sent volunteers into schools to teach distance learning, video conferencing, Google Classroom, Microsoft Teams. Not just one or two products, but all the platforms those schools wanted from us. Then we pushed it a lot into the pedagogy part of it, how to teach online, how to assign homework. We then also helped the Ministry of Education allocate funds for schools to provide some hardware to parents who didn’t have hardware at home.

I’m proud of the speed of that help, in addition to the result. It wasn’t something we would start thinking about in March, write a grant application in May, get some funding for it in September and start implementing it in January. From the moment schools closed, we went out and did real training within three days. That nicely shows the potential of the community that’s out there and when you find a strong idea, people can get together enough to do great things very quickly.

The second example is also related to the idea that things can be done quickly, although its two projects actually. The official Ministry of Health website on coronavirus, coronavirus.mzcr.cz, was created by Česko.Digital, even though it shouldn’t be, because of course the Ministry of Health with its billions in its budget should have the money to create a website on coronavirus. But it does not have the in-house programmers to sit there and be available, and it did not have the time to put out a tender and have an external contractor make a new website according to the tender documentation. That would have taken half a year or so.

When the first lockdown took place in March last year, the Ministry of Health’s website crashed within about four hours and there was not a single relevant source of information in the Czech Republic about what was going on, apart from what journalists were writing from press reports. To make the matter worse, the 112 line, which people called when they could not get to the Ministry of Health website, logically went down as well. Then you could not even call an ambulance if you did not get through.

It took us only four hours to offer the Ministry of Health to sort it out. Then it took them another four hours to decide they want it, and another 18 hours later it was done. When we reached out to the community and said we wanted to help the Ministry of Health and get them off the hook, within three hours we had 200 programmers. Then we picked four of them, and they did it.

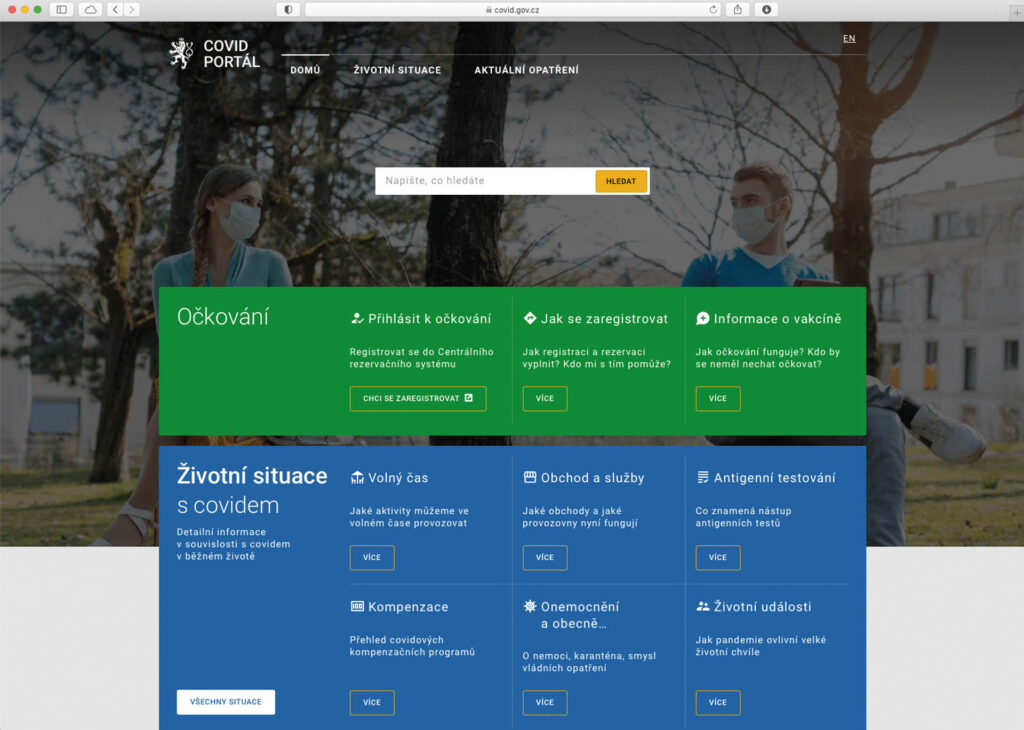

A very similar project that came up in the fall, covid.gov.cz, was a project that opposition politician Dominik Feri came up with, but he managed to convince Vladimir Dzurilla, the government’s IT coordinator, to do it. This was done as a project where both the volunteers and the civil servants came together and worked as a team. Not only is it a nicely done and clear website where you can find out what’s going on and what you’re actually supposed to be doing, but the essential thing is that it’s linked to the internal processes in the government and when a new regulation comes out, it actually shows up there.

Those were two very similar projects where we were actually pulling the civil service out of a bit of a jam that shouldn’t have happened. But it did happen and there was simply no way to respond commercially quickly enough.

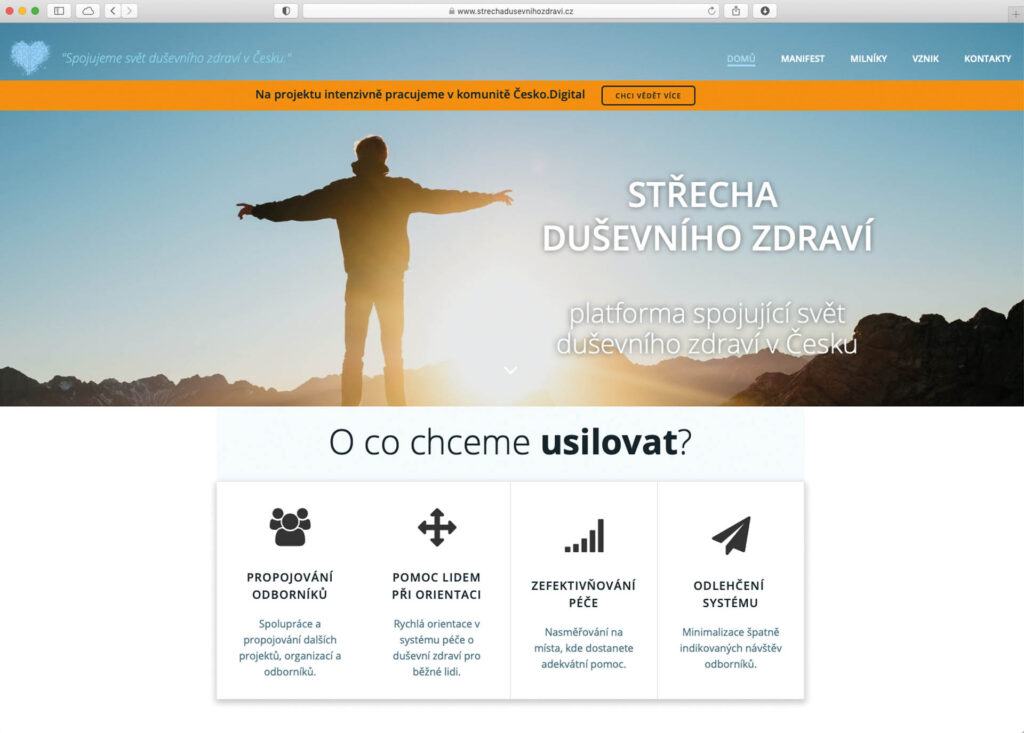

The third example is harder to pick because it’s a long list of nice projects, but it’s worth mentioning the Mental Health Roof (Střecha duševního zdraví in Czech). Of course, the mental health problem is even bigger now, not just in the Czech Republic but in most countries, than it has been for the last decade, and probably the most affected group is children, especially those from troubled families. They have no way of getting out of that environment because of schools being closed. The problems that exist in such families are only compounded and magnified.

Česko.Digital has managed to bring about eight organisations working in the field of mental health together into a single project. Its goal was to create one central portal, hence the roof, a kind of simplified online first aid line where these children can come and start looking for who can actually help them with what is bothering them, anonymously and without obligations. It’s not a happy thing to talk about, but it’s important.

That’s a nice selection of projects. Going back to the COVID thing, have you had anything to do with eRouška („eMask“)?

Česko.Digital had nothing to do with eRouška except that Nešetřil helped develop the app. That was my private activity, that’s why there is confusion. It’s because our first rule at Česko.Digital is that we only work on projects that someone wants us to work on. eRouška wasn’t wanted by the state administration, it came from below. And we don’t want to spend volunteer time on something that is uncertain to be used in real life. The moment you do it as activism and just say, here we’re going to program a new vignette e-store, here we’re going to do an eRouška, the risk of it getting thrown away is high.

That’s why Česko.Digital didn’t do this as a project, but in parallel a community of volunteers called COVID19.CZ was created and I, as a citizen Nešetřil, could afford to get involved. I felt this was an extremely meaningful activity. And I was very pleased that we were even able to be pass it on to the state and that the programmers from NAKIT (National Agency for Communication and Information Technologies) have taken the open source over and are developing it further.

This is quite precedent-setting already in that the state administration doesn’t know how to work with open source and feels that maybe it actually can’t. eRouška has remained open source, which to me is critical also in terms of auditing and trustworthiness that it’s not abusing private data. Then there’s the broader context. If the state administration can’t explain and market eRouška, if they can’t ensure that it’s deployed in sufficiently scale, then we can both calculate what that leads to in terms of the likelihood that our risk contact will be covered by the app.

However, at Česko.Digital we have a principle that we try to approach conflicts constructively and that our role is to look not for why it can’t be done, but how it could be done. There are plenty of people who point out what the state is doing wrong. That’s also a useful role, both as media and as some kind of watchdog, but the job of Česko.Digital is to help develop and implement things.

If you want to get involved too, check out https://Česko.Digital

Links to projects and organisations mentioned in the interview:

OSF Foundation

Učíme Online (We Teach Online)

Střecha duševního zdraví (Mental Health Roof)

COVID portal

NAKIT (National Agency for Communication and Information Technologies)

APIARY

More interviews with Jakub (in Czech):

Proti Proudu: Jakub Nešetřil pomáhá budovat lepší Česko s projektem Česko.Digital

Forbes: Necítím se bohatý díky penězům jako takovým, ale díky svobodě, říká Jakub Nešetřil v podcastu

Svět chytře: Jakub Nešetřil vydělal miliardy, teď s dobrovolníky v Česko.Digital mění život v Česku

Podcast at peak.cz: Jakub Nešetřil (Česko.Digital): E-shop na dálniční známky je špička ledovce, bojujeme o desítky miliard korun

Mladý Podnikatel: Jakub Nešetřil (Apiary): Růst startupu, obchodní model, začátky v Americe

CzechCrunch: Musíme mít na stát vyšší nároky. Česko.Digital dělá projekty, na které nejsou peníze, říká v podcastu Jakub Nešetřil

Lupa.cz: Jakub Nešetřil: Česko.Digital je moje nová životní etapa, přes IT chceme pomoci společnosti

Ekonom: Nevzdávat se je víc než mít nápad, říká zakladatel miliardového start-upu Apiary Jakub Nešetřil

CZECHSIGHT: Rozhovor: Jakub Nešetřil

Petr Mára: #25 – JAKUB NEŠETŘIL je zpátky. V Česku hrajeme první IT ligu!

Petr Mára: PODCAST#7 JAKUB NEŠETŘIL – Jak postavit miliardovou firmu, o pašování Macintoshe a o pomoci Česku

Proti Proudu – podcast Dana Tržila: 88: Jakub Nešetřil pomáhá budovat lepší Česko s projektem Česko.Digital