mensanthropist [ men-san-thruh-pist ] noun

a person, who actively participates in fulfilling one of Mensa’s objectives by fostering and utilizing intelligence for the benefit of humanity

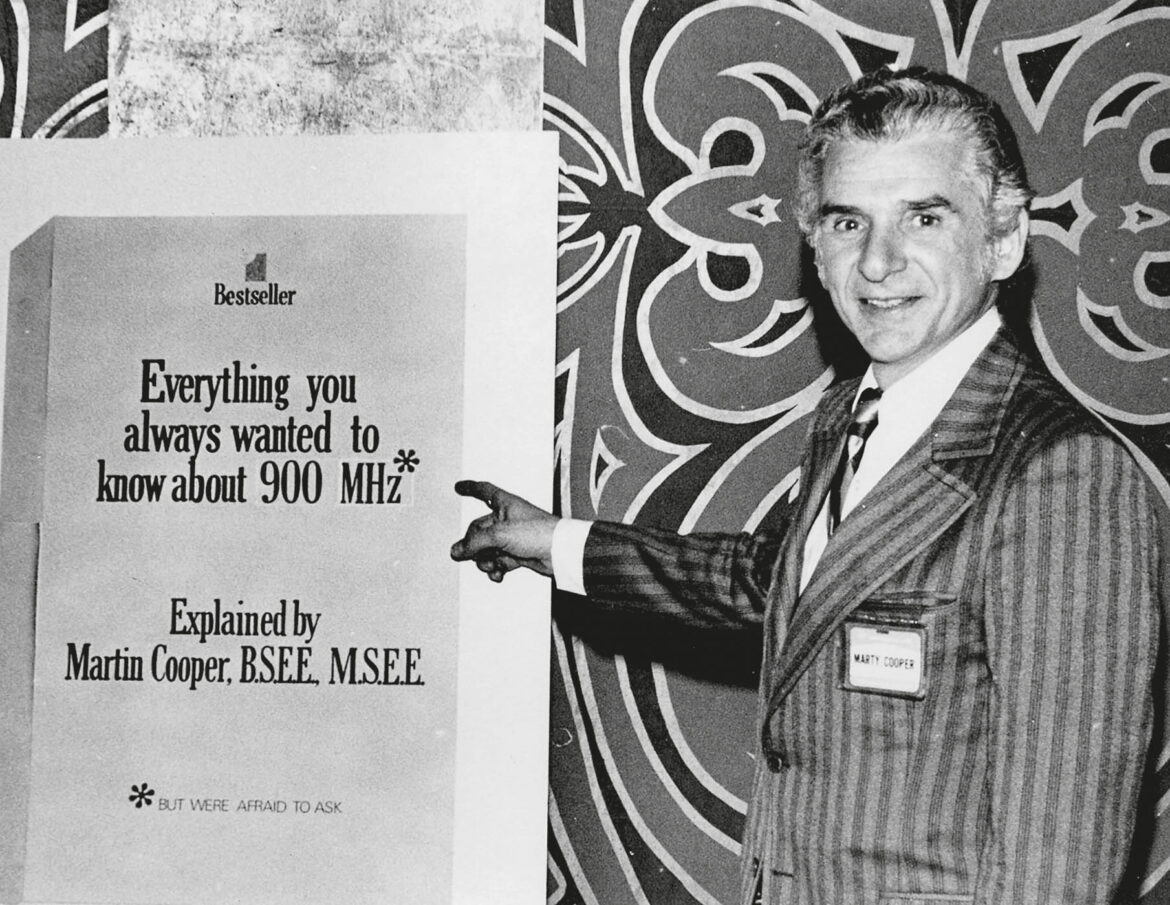

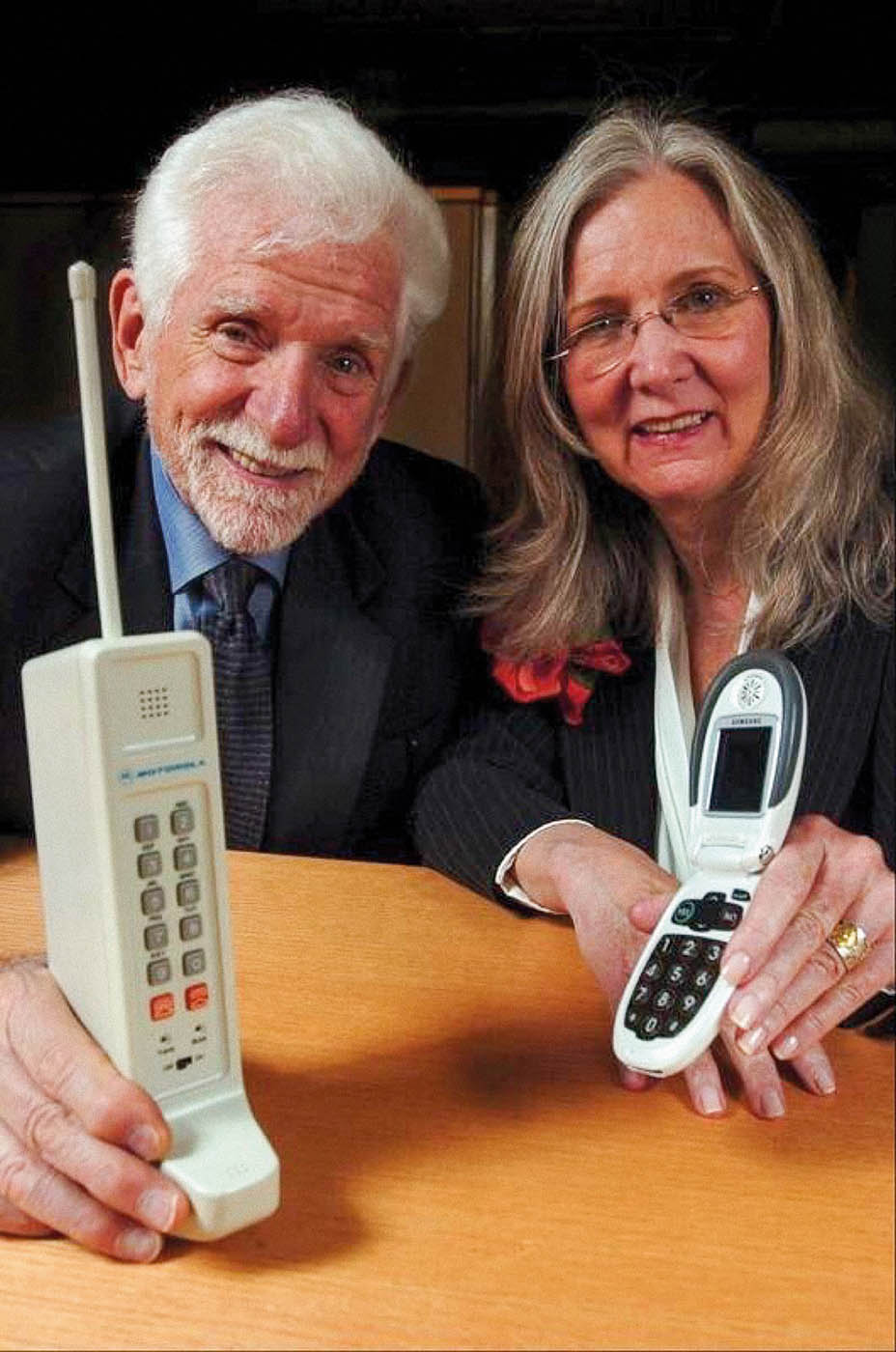

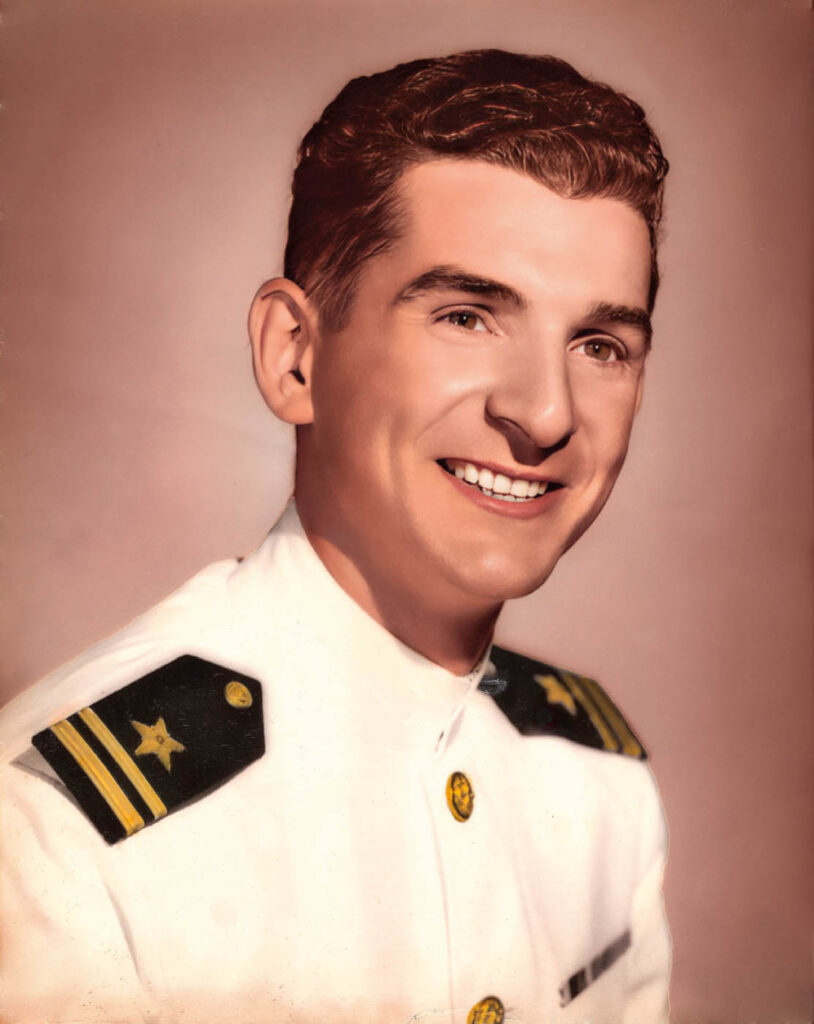

For this episode I had the pleasure to chat with Martin Cooper, an American engineer, inventor, entrepreneur, and technology visionary, known as „the father of the cell phone“. Asking everyone to call him simply „Marty“, born in Chicago in December 1928, Cooper patented radio-controlled traffic lights, invented handheld police radios, predicted radio frequency spectrum expansion trend, known by his name as the Cooper’s Law, invented the hand-held personal cell phone, and keeps innovating the communications technology since then.

Marty started our video call from his iPhone and one of his first questions was how we are doing in Czech Republic and whether we are nervous about what Russians are doing in Ukraine. Then he commented on it: „We are very fortunate here as we are far away from that conflict. But it’s all affecting everybody in the world, not just people in Europe. It’s just a shame. Two things that I think should not exist in the world today are war and poverty. There is no excuse for either one. If you’re an engineer like I am, your existence is based upon efficiency and making things work better. War is exactly the opposite, making people’s lives worse, not better. There no excuse for poverty either. We produce enough in the world. We are efficient enough. Nobody should ever be hungry.“

You’re best known for inventing the cell phone. What do you think about the today’s cell phones?

I think that the biggest contribution the cell phone has made is the ability to collaborate, we’re going to solve all the problems of the world by better collaboration. I also believe that all the social media will grow up someday and become a means of collaboration, and that will be very useful. Today they are more games than they are productive.

You invented the cell phone while working for Motorola. Did the fact that Motorola was founded the same year you were born have any impact on your decision to join the company?

I actually didn’t know that at the time, but joining Motorola was one of the luckiest things that I ever did. I am not a corporate person and Motorola for 29 years tolerated me and treated me extraordinarily well, even though I never really adopted the corporate persona. I don’t believe in the structure. To me, being disorganized is a basis of creativity. If you’re too organized, you will never have a new idea.

The founder of Motorola was a true entrepreneur. His first product was a heater for an automobile. It was successful, but then the heaters started blowing up. And that ended that business. His next product was to put entertainment radio in automobiles. An anecdote that he told was that he went to a banker to raise some money. The banker said, well, put it in my car so I can see whether it works. But when they were drilling a hole in the car, the car caught fire. His philosophy was to not fear failure and reach out. I believe I practiced that in my whole career at Motorola. My endeavors were not always successful, but enough of them were.

What made you join Motorola in the first place?

When I got out of the Navy in 1953 I went to work for a company called Teletype. They made mechanical printers called teleprinters. There was no electronics, just one electric motor, and the most clever mechanics that you could ever imagine. But they had an idea that somehow electronics were going to take over someday, so they hired me for their research department. But it became obvious to me after a while that it was not my type of environment there. As an example, you sat in a room with 100 other engineers. They had a bell which rang when it was time to take a break, they had a bell for lunch and a bell for going home. And when it rang, everybody stood up and went home.

Then I was approached by Motorola. During the interview they made me solve some technical problems. They hired me, and put me in their research department. There I discovered a different way of going home. Their quitting time was 5:00. Somehow somebody would start a conversation 10 minutes to five, and we’d stopped the conversation when it was finished. Even if it took 2 hours. People were engaged. They enjoyed what they were doing.

Were you ever also involved in Motorola’s supply of equipment for NASA’s space exploration programs?

No, not at all. I spent my entire career in communications. I made a telephone that would work in rural areas. I made a radio system that would control the traffic lights and things of that nature. At some point they moved me to work on the very first mobile telephone service called IMTS, which was a huge success in the United States. The second important thing I worked on was the radio pager, which still exists today but cell phones pretty much put radio paging out of business. Then I ended up starting a new division, where I worked on mobile phones.

In one interview you said that your goal with the handheld cell phone was to set people free from being trapped in cars or homes. Was it your personal idea or was it your assignment to come up with with the technology to allow that?

Nobody ever assigned that to me. My true inspiration was the comic called Dick Tracy. Tracy was a detective and had a wrist phone he could use talk to all the other policemen. Our objective was always to have a two way radio on your wrist. And when I succeeded with that, Dick Tracy came with a two way video phone. The concept of freedom came from businesses that could not function without controlling their moving resources.

Then the Bell System, who were the biggest company in the world by every measure – sales, profits, the number of people, announced that their people had invented a concept called cellular. That had happened in 1947 and now in 1969, they were going to execute, which gives you an idea of how slow the Bell System was. Their idea of freedom was putting these cell phones in cars, which to us was ridiculous. People spend maybe 5% of their time in the car. Their second principle was a monopoly. They had a great deal of influence in the FCC, so there was a possibility that they could win and become the only provider.

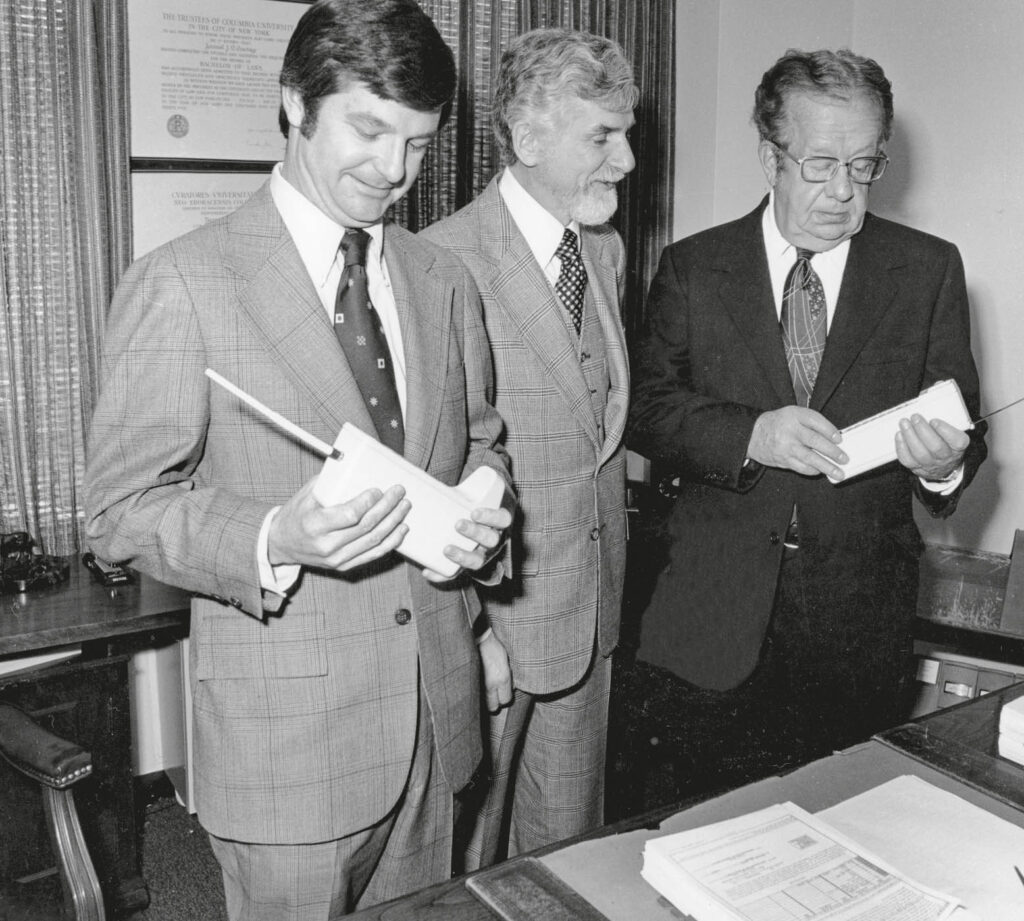

Of course they would have put us out of business. So our company went into battle with the Bell System. In 1972 the FCC was about to make a decision. We were frightened that they would make the wrong decision, so our management decided to do a big demonstration of two-way radio. I said we’re not going to get anybody’s attention with a two-way radio demonstration. But I believed we could build a cell phone that people could carry with them. They said: „We are already scheduled to give a demonstration in New York four months from now. If you can build a cell phone in four months, we will support you and you can have whatever resources of the company that you want.“ And that was the beginning.

We were successful in demonstrating the handheld phone on April 3rd, 1973. But it took ten years of battling between Motorola and the Bell System before the FCC finally made up their minds that this is going to be a competitive business and that the market will decide what the technology is worth, not a monopoly like the Bell System.

I read that the commercial release was in 1983. Then you left Motorola and founded your own company?

I started my first company in 1983 and in 1984 I left Motorola, just about the time the cell phone became public. Then my wife and I started several businesses. With one of them, we put cell phones in taxicabs and limousines.

Of course, that business didn’t last very long, but we had several other businesses that were more successful. In 1992, I and several of my colleagues started a business called ArrayCom, which created a cellular technology that only now is being adopted. We are way ahead of the rest of the industry. If you have been reading about millimeter waves, 5G, they use the thing called smart antennas. And that’s what our concept was in 1992.

In your interview for BBC in 2013 you mentioned that the industry has innovated in the wrong direction, focusing more on novelty instead of resolving the fundamentals. Have you noticed any change in the right direction since then?

It is a travesty, that the emphasis of the carriers is talking about a future business. They think that their future is the Internet of Things. Why do they think that? There are only 8 billion people in the world and the growth of population is slowing down. But there is no limit to the number of things. So they’re all excited about it, while they have not finished the job of the Internet of people yet.

I say the purpose of technology is to make people’s lives better. You don’t start out with a technology based upon the technology itself. You have to know how it’s going to improve society.

You cannot get educated today without having full time access to the Internet. If you need some information, you look it up immediately. If you want to collaborate, you do it instantly. But our educational system is obsolete. Lectures are absolutely the worst way of communicating with people.

I have a belief that any person’s education should be formed by that person. Teach them how to use the tools. Teach them how to access all the information of the world, give them guidance. That’s what teachers should do.

Do you think that StarLink is going in a better direction by bringing connectivity to places where was no coverage until now?

I say emphatically no. The most important reason is that satellites don’t work inside a building or a forest. So they do not provide very good personal communications. My second reason is that satellites are too costly. Even today, Elon Musk is charging 110 U.S. dollars a month for using one of their satellite receivers. For people that live in rural areas, connectivity shouldn’t cost more than $5 a month.

Education in any democratic country has to be for everybody. Some people will be more clever than others, but everybody should have the opportunity to gain an education. Every cell location has to have a source of access to the Internet. For that purpose, satellite, fiber, cable, those things are useful. But the last mile of education requires low cost communications.

Where do you see the mobile communications going in the next few decades?

I see the phone moving in two directions. One is personalizing it to its use. One of the biggest uses is education, but another one is health care. Why not put sensors on your body, that are determined by your genetic background? If you have a propensity for congestive heart failure, you can have a sensor that’s looking at your heart all the time. If we can have sensors on our body that detect these failures before they become serious, there is a potential to eliminate diseases.

My cell phone is a piece of plastic and metal. It’s flat. My body is curved. I have to hold it up in a very uncomfortable position. It doesn’t make any sense as a phone. So the future phone, I think, will be something that’s close to your ear. It’ll be embedded under your skin and powered by your body.

We ought to optimize all the features of the phone. The only way to do that long term is to have an artificial intelligence in the phone that looks at your habits, desires and needs, and creates or selects whatever applications make you comfortable and make your life better. It could look through all these 4 million applications to find the right one, so you don’t have to do that. People should not adapt to the tools. They should use the tools and the tools should make their lives better.

If you look at a little bit farther future, do you think that maybe in the next 200 years we will actually learn to use the technology that we have in our body and communicate around the world without external devices at all?

Sooner or later that can happen. But I am not sure it will really happen this way. The cell phone can already do things you can’t do. It has a microphone that can hear things you can’t hear. The camera can see a much broader frequency range and higher resolution then our eyes. So a little by little, the cell phone is taking over all of your functions. Someday it will figure out, maybe I don’t need HOnza because as an individual by myself I’m much more capable than any human being. We’re only at the beginning.

Have you ever been worried about your inventions being used in a wrong way, or have you always been an optimist, believing that humanity will learn from its mistakes?

I’m an optimist. I do, however, observe all the ways that cell phones are being used that are not in the public interest. Criminals are now managing their crime using cell phones. People are crossing the street with traffic and they’re looking at their cell phones. In a restaurant people used to sit around the table communicating with each other. Now they’re all sitting there looking at their cell phones.

When you have something new, it really requires a big cultural change. I have an abiding belief in people and humanity. I think people are going to learn how to use these tools and the tools will produce more good than bad. But it’s going to take a generation or two for people to learn how to do that.

One of the big problems of today are security and privacy threats. We are being asked for two factor authentication, three factor authentication, thousands of passwords. I see how how really difficult to handle this is for older people. Do you have any idea how to solve this problem?

It’s not just older people. Simplicity is something that everybody should appreciate. User interface is a crucial element of engineering, and we don’t teach that to engineers. We have a new concept called human centered design. And that is where everything should start. Everything that we do should be based upon humans and how they will react to these things.

I have one obsession. I really hesitate to use any device without first understanding how it works. Do you have a similar need?

I have to say that both of us are inefficient in this regard. We’re wasting time. We shouldn’t have to understand that. This has been brought to my attention in a very meaningful way, because there were two things that I wanted to understand that I did not. One of them is quantum mechanics and the other one is blockchain. I really have spent a lot of effort working on both of those, and I have to tell you I gave up.

For entertainment, you’re right. I do enjoy doing things. But in my home, I finally have hired a handyman. All my life, I have fixed everything in my house. But last year I started to realize that I am wasting a huge amount of time fooling around with things where I’m not learning anything anymore.

What you think about human intelligence and Mensa?

I joined Mensa when I was much smarter. It must have been in my early thirties, more than 60 years ago. At that time we had to take a test at home and mail it in. This was way before there was an Internet or cell phone or anything like that. My wife also took the test with me. When the results came in for her reporting an IQ of 150, she was afraid that I would be unhappy if she would be smarter than I was. Of course she was wrong about that, I would be very happy in fact. But two days later, my result came in and it was 152. So at least I satisfied her.

I really had big hopes for my Mensa membership, but I’ve always just had other distractions that have kept me from participating. I’m very proud to be a member, not just because my IQ happened to be the right number, but because I have an enormous respect for the things they are doing to help society. And I am a little ashamed that I have not participated in that.

Everybody should have a responsibility for using their talents to make the world better. That is why I am so passionate about education. I think that if an educated population will not permit poverty to exist, they will prevent war to exist, it will be making our society more efficient and better for all people.

Marty, You’re just turning 94 and you don’t seem to be any less busy than decades ago. What is your personal recipe for longevity?

Exercise. You have to do three things. You have to exercise your mind, your body, and your ability to communicate with other people. And probably the most important one is the last one, believe it or not.

That’s a scientific comment, not just an opinion. They did a study in Italy where they found an area surrounded by mountains. People from there didn’t travel very much, but their average lifetime was 12 years more than people in the rest of Italy. So they sent a bunch of scientists in to examine this. And they discovered, first of all, these people tended to be obese, they drank a lot of wine. The only characteristic they could find that was unique was that they had very strong family and social ties in their community.

So those three things have been crucial in my life. I was still running when I was 80 years old. I only stopped skiing when I was 88. I still workout three times a week with the dumbbells and I go walking. And I so much value meeting people, who ask me hard questions and are patient enough to listen to the answers. So that’s my recipe.

Links:

Wikipedia: mensa.click/vw

Britannica: mensa.click/vx

Dyna LLC: mensa.click/vy

InfoWorld 2000: mensa.click/vz

BBC 2013: mensa.click/w1

IEEE 2015: mensa.click/w2

National Academy of Engineering 2021: mensa.click/w3

Article at inSmart from 2021: mensa.click/w4

TEDx Talk DelMar 2010: mensa.click/w5

TEDx Talk San Diego 2011: mensa.click/w6

TEDx Talk Hasselt University 2013: mensa.click/w7