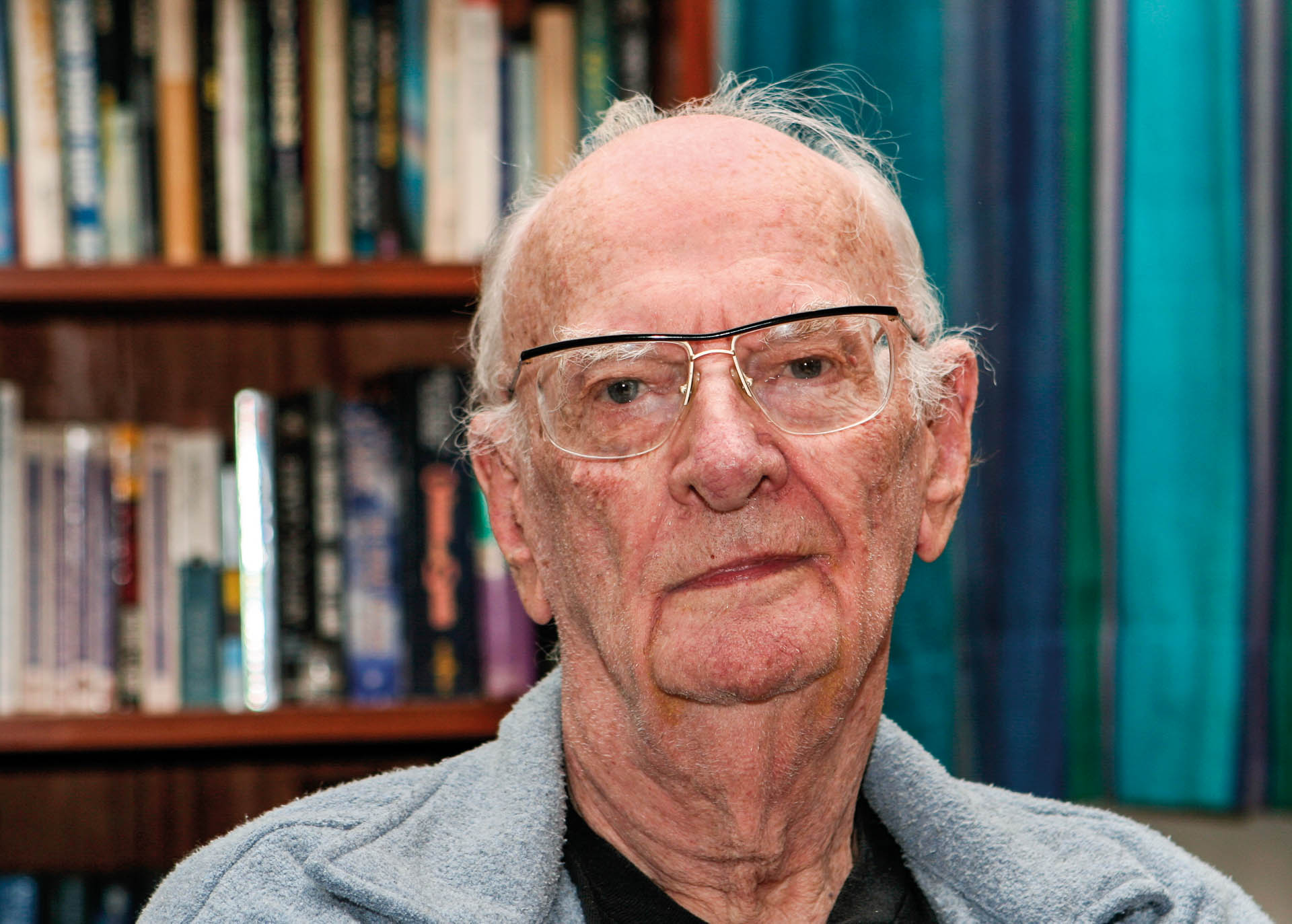

Arthur C. Clarke in his house in Colombo, Sri Lanka, 2006

source: Coffe Gitanes, Wikimedia Commons

mensanthropist [ men-san-thruh-pist ] noun

a person, who actively participates in fulfilling one of Mensa’s objectives by fostering and utilizing intelligence for the benefit of humanity

In this episode, I chose to introduce a writer, futurist, and scientist whose ideas have become so essential that many of us might not even find our way home from work without them. I first encountered him as a high school student when a TV series he hosted, The World of Strange Powers, aired, focusing on paranormal phenomena analyzed with strict scientific skepticism. Later, as I finished high school, I received his book Rama II and became completely hooked on his work.

Clarke’s Youth

Arthur C. Clarke was born on December 16, 1917, in Somerset, southwest England. He grew up on a farm, evolving from a fossil collector to a stargazer who built his own telescope. But it was transmission of information, or communication, what became his lifelong passion. As a boy, he built a photophone, a device that transmitted sound using varying light intensity, an invention by Alexander Graham Bell and Charles S. Tainter from 1880. Around the same time, he also became fascinated by science fiction stories in Amazing Stories, an American magazine. His interest in science, technology, and imagination sparked one of the greatest science fiction talents.

Before WWII, financial hardship forced Clarke to quit his studies and take a job as an auditor for the Ministry of Education. During the war, he served in the RAF as a radar instructor, again close to his favorite field—signal transmission. In 1939, he wrote about the possibility of rocket travel to the Moon. In 1945, he followed this with a Wireless World article on how three satellites in geostationary orbit could deliver TV signal to any place on the planet. Though the idea of geostationary satellites wasn’t his, it was Clarke who proposed using them for signal transmission.

Unfortunately, Clarke couldn’t patent the idea because UK law at the time required two working prototypes for a patent filling. When his vision became reality in 1962, he lamented in an article titled How I Lost a Billion Dollars Inventing Telstar in My Spare Time. In later interviews, however, he often downplayed the missed opportunity, remarking that “a patent is really a license to be sued.”

source: lakdiva.org/clarke/1945ww

His 1946 essay “The rocket and the future of warfare” earned him a scholarship by discussing rockets carrying nuclear warheads. He used it to graduate with honors in physics and applied mathematics from King’s College London in 1948. That same year, he became a professional writer, selling the story Rescue Party to Astounding Science Fiction for $180. His first major work, Against the Fall of Night, came soon after and was later revised as The City and the Stars.

His 1951 book on space exploration was used by Wernher von Braun to convince President Kennedy that lunar travel was possible.

Clarke as a Sci-Fi Author

Clarke’s second most famous technical idea (after communication satellites) is the space elevator—a structure anchored to Earth and extending into orbit, allowing access to space at the cost of about “$100 worth of electricity.” In a 1997 interview with Roger Ebert, Clarke joked that a return ticket would cost only $10 because gravity would recover most of the energy. He affirmed in the interview that he considered the concept feasible, predicting that one day we’d build it and open the door to the stars.

He explored the space elevator in detail in The Fountains of Paradise, inspired by Sri Lanka, where he moved in 1956 for scuba diving and stayed for 52 years until his death.

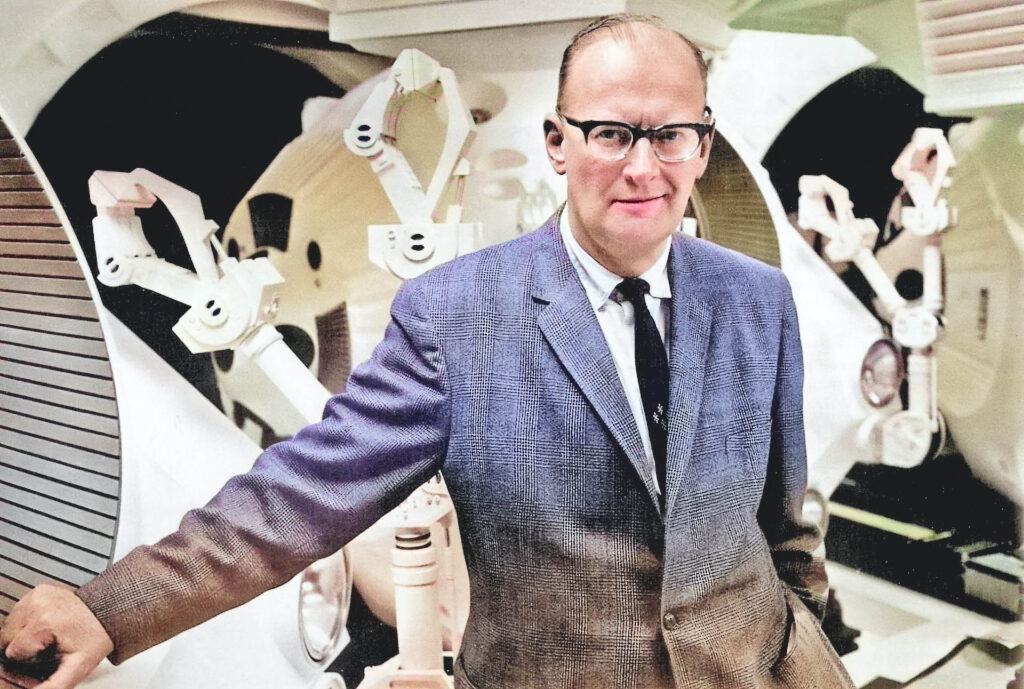

His best-known work is 2001: A Space Odyssey, released both as a novel and a film directed by Stanley Kubrick. Interestingly, the film wasn’t based on the book. Both developed in parallel, with Kubrick and Clarke inspiring each other. A lesser-known fact is that the intelligent computer HAL 9000, which was the heart of a spaceship and playing a key role in the story, was written into the book as originating in 1997, while the movie places its creation in 1992.

source: ITU Pictures, Wikimedia Commons

The story spawned sequels 2010: Odyssey Two, 2061: Odyssey Three, and 3001: The Final Odyssey. While these are often seen as a series, Clarke admitted in an interview that they actually occur in parallel universes. If you’ve read them before, this might be a good reason to take them out of the bookshelf again.

When asked whether he can imagine an invention so dangerous that its inventor would decide to keep it secret, Clarke answered that the most scary invention would be the time probe from his 1967 book Time Probe. It’s an idea of a technology that could reveal anything from the past, eliminating all secrets and bringing total transparency. Clarke doubted humanity could survive such a discovery. Interestingly, the book appears to have never been translated into Czech and is missing from most published Clarke bibliographies.

Czech sites like databazeknih.cz or cbdb.cz list 51 books, where, besides the “four-part trilogy”, the Rama series of books drives attention. Rama is a massive alien spaceship suddenly appearing and silently passing through our solar system. The first book, Rendezvous with Rama, was followed by three co-authored with Gentry Lee, and then two more written by Lee alone.

Clarke considered The Songs of Distant Earth his best novel. Though never filmed, it inspired multi-instrumentalist and composer Mike Oldfield to creating a music album of the same name in 1994, published on a CD-ROM containing Clarke’s foreword and futuristic animations depicting some fictions places from the book.

He is regarded as one of the “Big Three” sci-fi authors, alongside Robert Heinlein and Isaac Asimov, former long-time vice president of Mensa International. Asimov once said that “the only people he ever met whose intellects surpassed his own were Carl Sagan and Marvin Minsky,” while he described Arthur C. Clarke as the only writer who made him uncomfortable. As a biochemistry professor, Asimov could dominate conversations by steering fiction writers into science and scientists into fiction. With Clarke, who excelled in both, that didn’t work.

Many ideas from Clarke’s books came true yet during his lifetime. Even the modern World Wide Web was inspired by one of his short stories. Can you guess which one?

Arthur C. Clarke was a technical optimist. His stories envisioned humanity’s advancement, grand discoveries, and collective consciousness. Yet he didn’t ignore risks of technological advancement. In an Asia Week Magazine essay, he coined “cyberclysm,” pondering who would change our lightbulbs when we’re all plugged into entertainment devices. Who would run the Earth?

Clarke’s Predictions of the Future

In a 1964 BBC Horizon special, he said: “The only thing we can be sure of about the future, is that it will be absolutely fantastic… It will be possible in that age perhaps only fifty years from now for a man to conduct his business from Tahiti or Bali just as well as he could from London… one day we may have brain surgeons in Edinburgh operating on patients in New Zealandd… The most intelligent inhabitants of that future world won’t be men or monkeys, they’ll be machines, the remote descendants of today’s computers.”

In a 1976 AT&T Monitor interview, he described the ideal communication device as “a high definition TV screen with a typewriter keyboard through which you can exchange any type of information, send messages to your friends which they can read when they get up.” A machine communicating via audio and video, and displaying globally filtered information based on personal interests, rather than what newspaper editors think is worth telling us.” Does this remind you of anything?

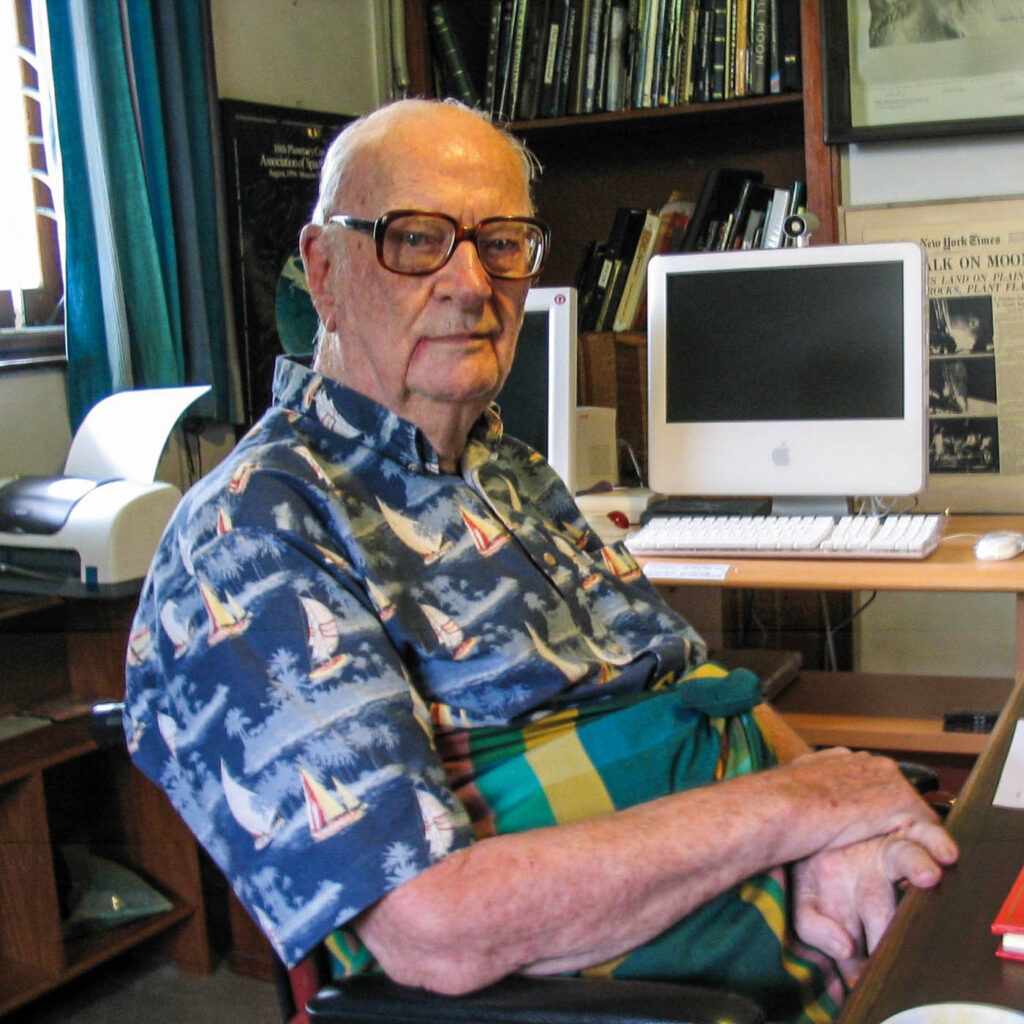

source: Rob Croes for Anefo, Wikimedia Commons

In that same interview, he predicted that travel would become recreational rather than necessary. What would he think of how the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated that shift?

He also had views on smartwatches. By 1976, he was already reflecting on their pros and cons, predicting they’d soon allow phone calls. He saw this affecting the whole society, from the negative impact of being available to anyone, anywhere and at any time, to this accessibility saving thousands of lives.

In his 1997 chat with Roger Ebert, Clarke estimated that the technological progress he forecasted in 2001: A Space Odyssey was delayed to around 2030 due to a stagnant space exploration program. At the time of writing the novel between years 1964 and 1968, NASA had planned to send humans to Mars in the 1980s.

In the 1990s, Clarke wrote: “The dinosaurs became extinct because they didn’t have a space program.” In a 1999 Discover Magazine interview, he noted that we now understand comets and asteroids shaped history and soon we’ll have the tech to avert such disasters. He predicted that within a century, we could reach 90% the speed of light and that “the nearer stars won’t seem much farther away than the antipodes were to the first ocean voyagers.”

Clarke’s Final Years

He spent his last 20 years in a wheelchair. In 1962, he was nominated for the UNESCO Kalinga Prize for the Popularization of Science. In 1986, he received the Damon Knight Memorial Grand Master Award from the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Association, and in 2000, he was made a Knight Bachelor “for services to literature.” He died in April 2008, shortly after turning 90.

In his reflections for his 90th birthday, Clarke celebrated 50 years of government-funded space research and anticipated the next 50 years would be led by commercial spaceflight, with thousands of people traveling to Earth orbit, the Moon, and beyond. In his words, mobile communication, developed in just a quarter of century, “is turning humanity into an endlessly chattering global family. Communications Technologies are necessary but not sufficient for us humans to get along with each other. Technology tools help us to gather and disseminate information but we also need qualities like tolerance and compassion to achieve greater understanding between peoples.” He named the 20th century “the most barbaric in history” and he wanted to “see us overcome our tribal divisions and begin to think and act as if we’re one family.”

In his farewell video, Clarke voiced three final wishes. The first was to witness proof of extraterrestrial life. The second was to see the humanity’s shift away from fossil fuels to clean energy. His third wish was establishing lasting peace in Sri Lanka, his adopted home, where he lived for fifty years and half of that he witnessed a civil war, separating the country.

The last who Clarke provided interview to, was in January 2008 the prestigious magazine Spectrum, published by the IEEE organization whose mission is “to foster technological innovation and excellence for the benefit of humanity.” There he noted his inspiration for geostationary satellites came from a Martian moon believed to be in stationary orbit, although today we know neither Phobos nor Deimos are areostationary.

Though proudest of his geostationary satellite work, Clarke viewed the space elevator as equally important, even from his deathbed. According to him, the space elevator will be built “about 10 years after everyone stops laughing.”

When asked if he had some advice for young science enthusiasts, he said: “Read as much as you can about the whole field of science and decide which particular subject rings a bell, and go for it.”

Arthur C. Clarke left behind a vast archive of manuscripts and notes, named “The Clarkives”, curated for some time by his brother Fred. Some personal diaries weren’t to be published until 30 years after his death. If released, what might they reveal in 2038?

source: Amy Marash, Wikimedia Commons

Web links:

Future prediction pro BBC from 1964: https://mensa.click/u9

Interview for AT&T Tech Channel from 1976: https://mensa.click/ua

Interview about artificial intelligence with Roger Ebert from 1997: https://mensa.click/ub

Interview for the Discover magazine from 1999: https://mensa.click/uc

90th birthday reflections: https://mensa.click/ud

Last interview for IEEE Spectrum (available to members only): https://mensa.click/ue

Brief biography at the London King’s College website: https://mensa.click/uf

Saga magazine article from March 1997: https://mensa.click/ug

Wikipedia in Czech: https://mensa.click/uh

Wikipedia in English: https://mensa.click/ui

Probably the last maintained archíve of the no-longer functional arthurcclarke.org website: https://mensa.click/uj

[Update: The website is now working again, maintained by the Arthur C Clarke Trust in Sri Lanka]