mensanthropist [ men-san-thruh-pist ] noun

a person, who actively participates in fulfilling one of Mensa’s objectives by fostering and utilizing intelligence for the benefit of humanity

I think one does not become a mensanthropist to become a mensanthropist. It just somehow comes out of how he lives and what he considers his life mission. And how can we help humanity more effectively than by inspiring others to do the same? That is why I have dedicated the next part of my series to a man who, although he has only been in the world for 32 years and a Mensan for only a short while so far, has already managed to start several activities in very different fields, all with the aim to inspire.

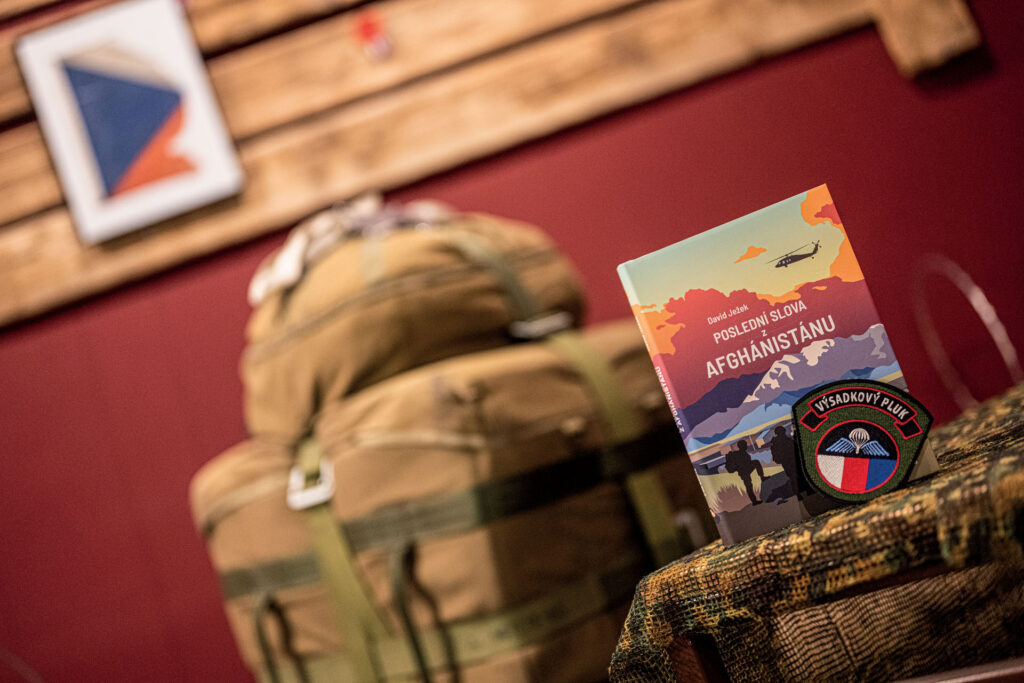

David Ježek was born in 1992 and despite praying for the abolition of compulsory military service during his childhood, he joined the army at the age of 25, completed a mission in Afghanistan, a walking pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela, a stay in the dark, a CZECHMAN sports competition, wrote a book and published a podcast (not only) about philosophy…

David, who are you? Where did you come from? What has your life been like from birth to now?

I was born in Prague but moved to Tábor due to family reasons. I grew up there from seven to eighteen and studied physical education and sport at the University of South Bohemia in České Budějovice. After graduating, I returned to Prague to study for a master’s degree at the Charles University’s Faculty of Physical Education and Sport, where I’m currently working on my rigorosis procedures. I also study at the University of Moravská Třebová in population protection.

As for the army, I would like to tell a heartwarming story about my dad, my grandfather, and my grandfather’s dad being soldiers and everything leading me up to that, but the reality is quite the opposite. When I was a kid, I even went to church and prayed for the mandatory military service to be abolished. It was more of a coincidence that a friend asked me right when I felt I needed a change in my life.

Joining the army really did change my life completely. Until then, I was the master of my time. I trained clients, taught school, and occasionally went to the pool to get a tan as a lifeguard. As a trainer, I was basically the one „hazing“ others, and suddenly the tables were turned. People who didn’t even know who I was started yelling at me for having my blouse buttoned wrong, being a minute late, that sort of thing. That was a big change.

During my military career, I also started new projects. I began writing a book. I’m involved in snowboarding as a referee at the highest level. I’m involved in charity events. And my new podcast takes up a significant portion of my time.

I started the podcast mainly because some of the topics I cover there are my future degree exam questions. So I figured that developing a script for the topic and learning to talk about it is probably the best possible preparation. And if it interests me, because I like to listen to this stuff in the car, for example, it might interest someone else as well. I’m not paying for any advertising to promote it. It exists primarily for my own purposes. And if somebody’s interested in it, that’s a bonus.

You say one question got you into the army. What was the magic question?

A milestone for me in my student days was the movie Yes Man with Jim Carrey. I wasn’t really going anywhere at the time, I was more of an introvert. But after seeing that movie, I started to be a little more outgoing. I started answering yes to questions and challenges more often. So when a friend asked me, „Do you want to join the army with me?“, I said, „Okay.“

His reason to do it was the same as mine. He needed a change. He was a classmate of mine both in České Budějovice and at the follow-up studies in Prague. I describe him as Štěpánka in my book and he is actually my best friend. We went on the same tour, together we completed the basic training course and the selection process for the paratroopers in Chrudim. Actually, even during the mission we lived across the street from each other, so from then on we were together practically every day.

What led you to the need for change?

I was working as a trainer in five or six different fitness centers, and I was actually running everything myself the whole time. In a way, it was great because I was doing sports from morning to night. On top of that, I was teaching at a school and after a while it started to wear me out. I realized that I had practically no free time and I didn’t even enjoy sports that much anymore.

What sports did you enjoy the most as a child?

I went to Sokol regularly. I probably tried every sport that exists in some way. It was ice hockey, volleyball, basketball, I also played football for a long time, almost at a professional level. The other dominant sport for me was floorball. I think I got a movement base for virtually every sport thanks to Sokol. That versatility helped me a lot to handle gym school better than my classmates who maybe did one sport at the top but were great in only one area, whereas for this kind of school you need to be proficient in all areas.

Have you ever been tempted by IRONMAN?

IRONMAN tempts me. This year I completed Czechman. I wasn’t tempted before, but I was starting to feel that I should try it, especially since I bragged everywhere that I’m an all-around athlete. So I started a two-month training and when I accomplished my goal, I figured that sometime in the future I should probably do Ironman as well.

How does Mensa fit into all of this? And what made you take the IQ test?

I’m sure no one ever led me to it, but I always did well on these types of tests in school. IQ tests are part of the military entrance exam. In Chrudim, which is a selective service, it’s even a bit harder than just „getting into the army“. So I thought it would be nice to take the official Mensa test as well, to see where I stood. I always wondered if I was weird or if I was smart. And Mensa told me that I might be weird, but in terms of IQ, it wouldn’t be bad… [laughs]

What convinced you to become a member of Mensa? Or did nothing have to convince you?

Nothing had to convince me. I do a lot of things because they suddenly start coming to me. For example, it happened to me that within two or three months, five people who didn’t know each other started casually telling me to try Mensa. That’s actually how it came to me.

What does it actually look like in real life with free time in the military? Someone may feel that the army will line up 100 percent of what they do, but to me it feels like it opened the door to those other activities for you because you do a lot. Where do you find room for that?

It’s certainly not as easy as it seems. One of the milestones for me was when I started to feel like I was getting stupid in the military. I’d start a conversation with someone, and a lot of times I didn’t know how to finish a sentence. Especially in the beginning, when all I had to do was acknowledge orders.

A soldier is just given a task and he has to do it. He doesn’t have to think about why he has to do it. Suddenly I was beginning to feel like I was almost stuttering when I wanted to say something. So I started reading a lot more and went back to studying. Then the preparation for Afghanistan started and I told myself that if I come back alive I will completely change my life and the first thing I will do will be to finish my master’s degree.

Fortunately, I came back, started preparing for my state exams and found that I was having a terrible time learning again. So I started to go to another school and do this bunch of projects. But it cost me having virtually no free time. I’m constantly having to organize something. For example, I’m also the president of the Czech Footbag Association, and now we want to organize the World Championships in the Czech Republic in two years. So I’m constantly doing something, but it actually came about after my return from Afghanistan.

What were your feelings about going on the mission?

They say a soldier doesn’t count on a mission until he’s actually there. We had it set up so that until we were on the plane, we were counting on that something could change. When it was getting close, a week before departure, my procrastination kicked in a little bit. Instead of writing my will in time, I ended up turning on my camera and shooting my farewell videos just a few hours before departure.

Emotionally it was a strange time, in a way I was looking forward to it, but of course I was also a bit scared, I was full of expectations and I didn’t know how to say goodbye to someone. My head was always set in such a way that nothing could happen, but I had to take into account that several colleagues had already died there, I even knew some of them.

I certainly had a healthy respect for what was to come. My book begins with a foreword, which is actually a transcript of a video I made of myself saying goodbye to life in case I never came back. This video would then go to my family and loved ones. I even shed a tear during the video, it was hard to imagine that I had died.

You mentioned that you were going to three schools at once. One is the master’s at the sport faculty, what are the other two about?

One is the rigorosis procedure at Charles University. That’s focused on philosophy. And then an electromechanic in Chrudim. Basically, something from every drawer. Actually, one secondary school, one post-secondary vocational school and one university. I’m trying to be kind of multitalented.

Do you think there can still be such a thing as a polyglot these days, that the human capacity is still sufficient?

I’m trying to prove that it’s possible, but sometimes I feel like it’s not. [Laughs] The truth is that the level in many areas is so high that if you want to be the best at something, you have to give it your full attention. My variety of activities comes from the fact that I always say, „You should do what makes you happy.“

What kind of projects do you do and what do you try to achieve with them? If your life were to end, what would you consider to be your greatest achievement right now that has fulfilled its purpose?

I consider my purpose to be that an outsider’s view of my life can inspire other people. Let’s say to work on their personal development, whether in terms of physical activity, spiritual or intellectual. What I consider as a proof that I am doing it right, and the reason why I believe in it and still continue to do it, is how many times I have had someone tell me that they have changed their life because of me, that they have started studying, for example. It’s always so nice to get feedback that just me doing what I enjoy can influence someone else.

I enjoy helping. As an example, all the profits from my book go to the solidarity fund. I don’t do podcasts to get famous. I do not just cover philosophical topics, I also discuss the lives of philosophers in a way that’s entertaining and helps students in schools. I’m not trying to tell people what’s right, but rather just to show a different point of view. I often try to get others involved in the philosophical questions, to write in their opinion. It’s a great feeling when I make someone think more about their life.

When you’re learning, does it take away energy, add energy, or is it balanced?

It’s a bit draining at first, but once I get into the flow, it’s like a burst of energy!

So it’s the podcast, the book, what’s next?

Then it’s the presidency of the footbag association. It’s a sport we’ve been trying to keep in the Czech Republic for a while. It has two branches – freestyle and footbag net. Freestyle is played with hacky-sack, where people kick it and do different tricks. Czechia is very successful in this sport. We also have world champions. It can be described in layman’s terms as kicking a small ball over a badminton net, while the ball must not fall to the ground.

I was also involved with the Arditi Scout troop for a while, but I had to leave that because I couldn’t manage the time anymore. It is run by soldiers from Chrudim in their spare time, basically trying to take the kids out and teach them how it used to be done. So they don’t look at their cell phones and play computer games. They just drag them off into the woods, teach them how to make fires and stuff.

And then the snowboarding. It takes me practically every weekend during the season. Just the preparation, like the international training in Warsaw. The sport is always moving on. For example, what was enough for an Olympic gold medal in 1998 might not even be enough to qualify in the junior categories today.

Where did the philosophy come from?

I wasn’t into philosophy before. When we had it at school, it was always lectured by an older gentleman who spoke in a monotone. I often fell asleep in those classes. But then I got into it on my own, based on my inner workings. I began to read about philosophy, I bought various philosophical publications, and suddenly found it quite beautiful.

It is a pity that it is often presented to students in an incomprehensible form, using complicated foreign expressions that students do not understand. The whole point of philosophy is to explore, but students often don’t even get to that point because they stop enjoying it before they begin to understand it. Schools teach history of philosophy. We just learn how it was, but the teachers don’t really teach us to philosophize.

Sometimes, even in the army, I think about everything. I try to figure things out so that maybe they can be done in a more meaningful way, because often something is being done just because it’s the way it’s always been done.

What are the chances of pushing a change through if you think of a better way?

Aleš Opata’s book Sám nejsi nic (You Are Nothing Alone) describes it beautifully. He tells us that when he took over as Chief of the General Staff, he had several projects he wanted to implement to move the army forward. But over time he was happy to push one or two through. It’s the same with me. However, I feel and believe that things are turning for the better and visionaries and people who are trying to change things for the better are getting their say.

What are you reading right now?

Three books at the moment, but I’m probably most focused on the philosophical novel Flock Without Birds by Filip Doušek. It’s not a light-hearted book, but the concept of how Filip has taken the work itself is fascinating. Another one is The Forest Within by Alena Mornštajnová. And then there’s Aristotle for the podcast episodes.

Do you read fiction as well?

Of course I do. I’m very fond of historical fiction. I’ve never been into history, but the saga Rytíři z Vřesova (The Knights of Vřesov) by František Niedl is my favourite. I also like fantasy. The Name of the Wind by Patrick Rothfuss, for example. But I don’t have a set genre, I’m happy to read anything.

As for podcasts, do you want to reveal what we can look forward to in the next series?

The second series of the podcast will end in mid-December 2024. When it’s over, I’ll do an analysis and recap of what drove the most interest. Anyway, in the next series, I will definitely focus on the Olympics, both Pierre de Coubertin and the Olympic idea itself. I have interviews with athletes lined up, but the main climax of the interviews will be tied around the military, philosophy, sociology and faith. For the moment, however, I will keep it shrouded in mystery.

What would you like to inspire Mensans to do? What could they do to make their lives more meaningful?

I guess it would tie back to how I try to live in such a way that I inspire someone so that they can inspire someone else. When I mention the various Mensa meetings somewhere, or that I’ve been to Switzerland where we visited CERN, the general public often think of Mensans as these weirdos who have no sense of humor. And that’s a great pity. Every time I met someone from Mensa, they were entertaining people.

What other Mensa events besides the trip did you participate in? What would be worth publicizing more?

I like just this interview we had, and the magazine itself, the way it’s designed. It often highlights interesting personalities and interesting people. I also like the cohesion of Mensans, that they meet regularly. It’s often to one’s advantage to bring in someone else who is not a Mensa member. I think it’s great that it’s not some closed elite. Personally, I miss more activities that would be purely focused on sports, there aren’t that many of those.

Have you considered kicking it off yourself and organising something?

I’ve even had the form open do an activity, but as I have a lot of projects it’s hard to fit it all together. It’s hard to plan something a month in advance because there might be a military event I have to go to. I don’t like it myself when someone plans or promises something and then cancels it at the last minute. But I believe I will organize a sporting event sooner or later.

What would you like to say to the Mensans in conclusion?

Think about what really makes you happy. What is the meaning of our lives. Because even just thinking about such questions can make our lives better.