mensanthropist [ men-san-thruh-pist ] noun

a person, who actively participates in fulfilling one of Mensa’s objectives by fostering and utilizing intelligence for the benefit of humanity

George Francis Simons, born in 1938, now living in France after a lot of travel, educated in languages, philosophy, liturgics, sociology, anthropology, psychology, and theology, spent most of his life as an interculturalist, helping thousands of people from different backgrounds learn about each other’s cultures and live and work together more successfully, thanks to understanding and accepting their diversity. Back in 1972 he developed diversophy®, an educational game he uses as a tool to teach students and trainees to handle conflicts and deal with challenges coming from multicultural living situations. diversophy® has since developed into a series of over 100 gamified instruments covering many different cultures, countries, languages, topics, and other aspects of human-to-human interpersonal, social, and political interaction. Here are highlights of our interview together.

George, you were born around the beginning of the World War II. How did it impact your life?

It was a terrible time. My parents were already older than most couples getting married today. People didn’t want to get married during the Great Depression because they feared they couldn’t afford a home and kids. The early days of my life were well marked by that time, even before the war.

My father was a real woodsman. Unlike many city dwellers, we lived in a small town, on the edge of a forested park. Dad would come back from a trek in the woods with all kinds of wild edibles that he was familiar with and a few fish from the creek. We didn’t go hungry! But when World War II came along, things changed. My dad got a job with a company that made bombsights and my mother with Thompson Products, assembling Tommy guns for the military. By the end of the war, my parents had saved up enough money to buy a house close to the center of our small town, Bedford, Ohio.

My mother’s immigrant father, Stanislav, had served as a blacksmith in the Russian army. He was Polish, but there was no Poland when he was there. As he often said, “Poland was crucified between two thieves”. He was a man who could build or fix anything. The basement of our new house became his workshop. I grew up helping him, sort of his apprentice. My other immigrant grandfather, Anton, had been a court tailor in Vienna and lived only four blocks down the street. He opened a tailor shop and was popular around town as “Tony the Tailor”. I never had store-bought pants until I was second grade in school. In front of our new home, my father built a prefab barber shop with help from my grandfather and me, where he worked until he retired. And that meant he knew everybody in town.

We lived in one of the “melting pots” of the U.S. I could leave the house, walk four blocks in any direction and people would be speaking another language. My dad would go fishing on the weekends with 4 or 5 his buddies, no two from the same country. On the way home, he would always take me to a different ethnic restaurant. Russian, Hungarian, Jewish delicatessen, etc.

My dad’s motto was, “Try anything at least twice–first time might be a fluke.” I believe this gave direction to my life and planted the seeds of my mission as an interculturalist. Dad banished fear and replaced it with curiosity, so that when I encounter something that’s different, I get attracted and want to know more about it, rather than letting the “fight or flight “prompts of unconscious bias, as they call it today, block me from new experiences. I don’t like the term “unconscious bias” because it sounds accusatory. Basically, it’s a normal function of our brain to automatically suggest what’s safe and what’s attractive and what’s not. George Lakoff called it “framing”, and I prefer that. So, my mission has been to help others replace fear with curiosity, doing intercultural training and using my games as ways of getting people to do that and connect with each other.

What I’m delighted about is that, nowadays, neuroscience has enabled us to realize that we are each a unified system. We’re not body and soul, mind and matter, the ghost in the machine. Our consciousness is part of our everything from our brain to our fingertips. When you and I do something together, experience something together, exchange something, we become more like each other because our mirror neurons are recording the same stuff. Thus my mission is to get people to connect with each other effectively, and that’s why people love our games.

Would you say that your father was actually the biggest influencer in terms of your career?

Dad basically embodied it and modeled it for me and as well as telling me about it. For example, when it was time for me to go to high school, dad said, “Let’s go shopping”. We went school shopping. He drove me to various schools that looked interesting, a military academy, a seminary, and so on. He was always making it my choice. Eventually, I wound up going to two different high schools and then several colleges and a seminary university as well. I got my master’s degree at Notre Dame University, then I got my doctorate at Claremont in California when I later won a fellowship there.

So, I was experiencing other cultures, even within the USA, at a young age.

To be somewhere new and to meet people who are different is an attraction rather than a threat. It was essential a part of my life and my work. After I graduated, I worked in a local church whose neighborhood was multiracial as well as multicultural. In the summertime we did programs for the community and ran activities for the local children. I worked at several colleges at that time, such as the Lorain Community College and Case Western Reserve University. Finally, I was invited to become a house director at Oberlin College, where I was responsible for a large co-ed dormitory.

I was found myself coaching young men who were deciding if they wanted to join the military during the Vietnam War or evade the draft by going to Canada. That kind decision was very touchy. I also hosted the local chapter of the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), which was considered a very radical left group at then. One day I happened to be in downtown Cleveland, Ohio and I saw truckloads of young soldiers clutching their rifles, heading to Kent State University, scared to death. They went to face protesting students their own age who put roses in their rifle barrels. The excursion ended in violence and death.

When I as awardeed my Danforth fellowship, I went to the West Coast, and earned my doctorate in psychology. There I got familiar with Gestalt therapy, which shaped my mind in new directions Gestalt is a very active, interactive kind of therapy, where you often have conversations with yourself. This became very relevant to what I’m trying to do making myself and others aware of our cultural identity and sharing it with other each other. In California I was invited to work in developing a program that was called Genesis 2, which wound up being used by over 3 million people.

How has your life and work changed since then?

A consultant hired me in 1979 because I spoke Spanish and French, so I suddenly wound up going international. I had had a great French professor, so my first vacation abroad was into France, and I think I’m living In France today because of that. Later, I discovered that I have a trickle of French blood because my grandfather on my dad’s side was a grandson of one of Napoleon’s soldiers whose name was Simon. In the next generation, as Croatia still used patronymics, it became Simonović. But, as you may know how the United States welcomed Eastern Europeans and Catholics, my father got tired of being called „Simonović, the son of a bitch“, and changed the family name to Simons.

Soon I started to set up my own training and consulting business. A guy who was very much interested in men’s issues came to interview me from California. We hit it off and, together started an organization that created workshops for men. Our big seller was “How to Love an Angry Woman”. This was right at the time when feminism was in sort of an adolescence and guys were complaining: “My secretary doesn’t like me anymore. My wife doesn’t talk to me anymore. My daughter sees me as an old, biased patriarch. So, what do I do?” We created a program (which ultimately became a book) and conducted these workshops in California and abroad.

In my practice, I ended up teaching communication and doing workshops until today. In 1982, I had an interesting adventure doing time management trainings for the Greek Management Association in Athens. I also worked for the Basque cooperatives in the north of Spain, and later became a vice president of a consulting firm that was doing programs on influence skills and negotiation and became a certified trainer of those programs. I did at least 50 or more of these programs for Procter and Gamble around the world and went back and forth to the Philippines teaching negotiation at the Asian Development Bank in Manila.

One of my weaknesses today is that I spend too much time curiously surfing the internet because you can find everything there nowadays. It seems like I am busier than ever. I imagine that I am digesting 200 times more information every day than I did when I was a graduate student in college. Back then I would have a notepad on my desk and jot down things I needed to look up. Then twice a week I would hike to the other end of campus, flip through the card catalog to identify books which might give me answers, then go to the stacks to peruse them. Now, I may know that an answer is in a book on a shelf right over my shoulder, but I’ll Google it quicker than I can turn and take the book down.

You mentioned in one email that you won a joke telling contest at the 1983 Mensa Pacific Congress. How did you get there? Were you a member of Mensa?

Yes, I was a Mensa member when I was living in Ohio. I can’t tell you exactly the years but for quite a few–somewhere around the 1960s. I often attended their regular events. I don’t have a lot of memories of those, but I do remember this wonderful congress event in New Zealand because I have a whole mess of photos from it… it was interesting and a lot of fun.

What did actually make you to do the IQ test? What was the first impulse to get tested for you?

This was done a long time before. It might have even been in grade school that we took a test. I can’t remember. Anyway, I knew that my IQ of 163 was adequate to join Mensa, but I didn’t know anything about it, until a friend invited me and I sort of went along and that was it. When I started traveling all over the place, it just sort of faded into the background.

Did you have a feeling that the high IQ was more helping you to succeed, or did it feel more like a handicap?

With or without the test, I was a good student. I was generally the top of the class on my way through grade school. And in high school, I was always number one or number two. I was a teacher’s pet, sort of exploited by them, because I knew how to touch type and run the mimeograph machine. This recognition of intelligence was good for my sense of identity and well-being.

Was it help or struggle for communication with your classmates?

Often the second. I had good friends in school, don’t get me wrong, but when it came in the academic area, then I was the smarty pants. I’m not a very outspoken person, though. I’m pretty much an introvert, but introvert in the technical sense. I get my energy from working alone. I don’t have any problem being sociable. Extroverts get their energy from the exchange with other people. I enjoy the exchange, but generally I wake up at 4 or 5 in the morning and I got 4 or 5 hours to myself to do the things I want or need to do. Generally, I’m available. I’m not a shy person, but I do need the alone time myself to integrate.

Are you still Mensa member today?

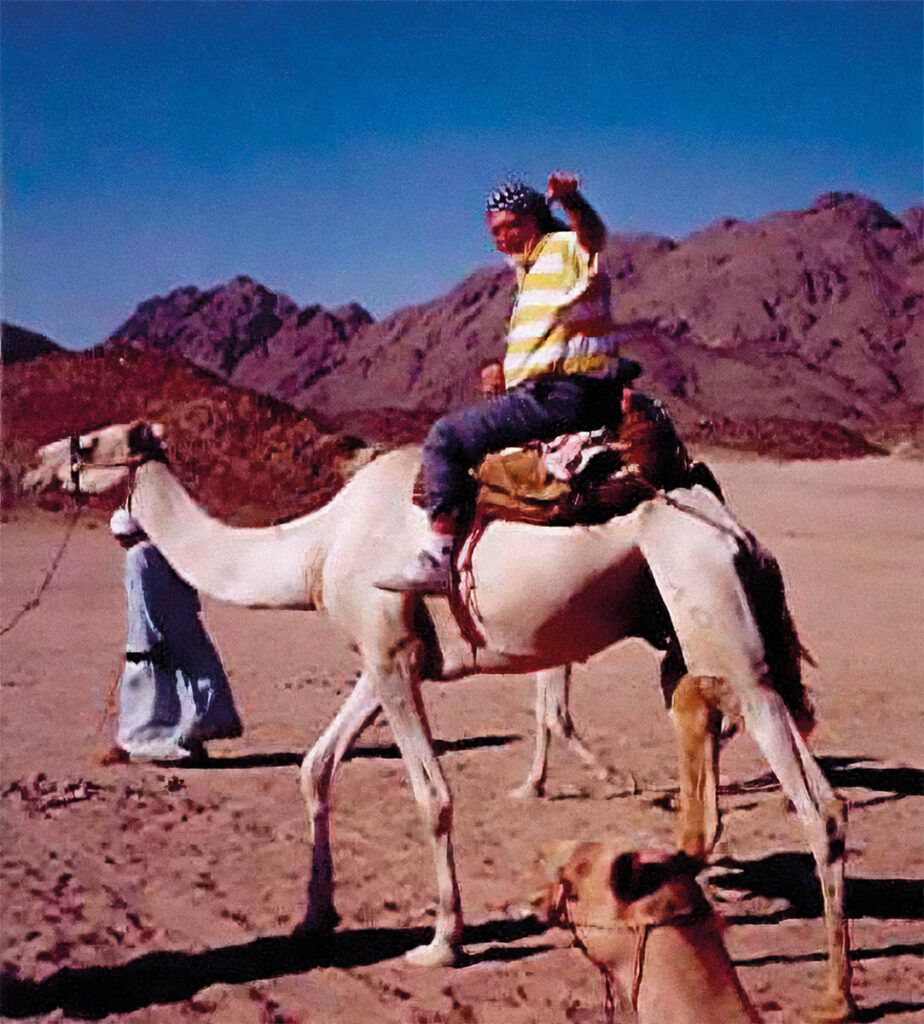

I have no idea where there’s a Mensa. I just lost track of the whole thing. Until COVID I did a lot of travel. I was in some other part of the world 60 to 70% of my time. I was so rarely at home that I’d wake up in bed and wonder, “Where am I?”. I’d been mostly abroad since the 1980s. I did an enormous amount of work in Indonesia and various places in Europe. I finally sold my home in the United States a couple of years ago because I never used it.

What was your take on your own gift that you are smarter than 98% of the rest of the world?

Taking care of people helping others preceded any consciousness that I was a bright kid. I didn’t have a what you’d call a radical conversion point of any kind. Everything just sort of grew gradually. I have colleagues that I work with, and a network of people that are very important to me, like working on these games and things. I had about 65 interns in my career, and they have come from 25 different countries so far.

When we get back to those diversophy® games you do for the last few decades, what do you see as the primary outcome?

The first diversophy® game I created was a response to the Workforce 2000 report that came out in the 1980’s. It was about dealing with increasing US diversity issues, what was going on racially and ethnically in the US workplace. When the US got involved in NAFTA, we added Canadian and Mexican cultures to our game content. Next, we did a game on gender and then it just kept on growing out from there. When we first started out, we thought the games were a good way of learning about others. But people playing our games let us know very clearly that the important part of this is not just learning information. We discovered that what happens is that people share their own stories and connect effectively with themselves as well as with each other. It ignites tremendous energy that both moves them to do things that are important interculturally as well as giving them the sense of community in doing it.

So how does diversophy® work?

Each game is a set of five different kinds of cards. Taking turns answering and discussing CHOICE, GUIDE and SMARTS cards, players learn about different cultural discourse, facts, and behaviors and the contexts where they can apply them. In our RISK and SHARE cards, we ask people how they would personally respond to various situations in their own and other cultures, what they would do and what might be the best practices.

So, would you say that one of the ultimate outcomes of playing your games is improving your empathy and understanding of different people and cultures?

Absolutely. It verifies that the current emphasis on storytelling is extremely relevant. People are using storytelling all over the place. diversophy® games have generated storytelling for the over 30 years. Basically, the game is a place where people tell each other bits of their stories, connect with each other, and gain more understanding and solidify empathy with the people that they’re playing the game with.

One of the topics that keeps appearing in my interviews is what a big shame it is that we still have poverty and wars in the world. So, you think that playing your games could help ending wars?

We hope so. Our games have become more and more focused on critical social and political issues. The two main game projects we are developing right now are on Populism and Decolonization. How do you decolonize your mind, whether you’re a colonizer or a colonized person? How do you deal with that power relationships that have been created and embedded often in your mind as well as in your genes? We have a potential to activate genes that were shaped by the traumas of our parents and grandparents. Apparently, these live about three generations, if I understand the findings of epigenetics correctly.

Last year we created a game which we called diversiDARE, a set of cards that focused on bringing up topics that people are afraid to talk about, creating a safe space for us to deal with more of the tough stuff. It’s easy to become a theoretical academic. What I’m always concerned about is exploring how research discoveries can be used to better the world I live in.

What do you think would be a cure to the war in Ukraine?

I wish I knew the answer to that. We did a series of games on Ukraine and the culture of the places where the asylum seekers are going to, helping both cultures understand each other. But this goes to the issue of populism, the „us versus them“ mentality and, of course, the fact that strongmen, whether we’re talking about Putin, Duda, Orban, or Trump play on fear. We need connect people in such a way that they’re not afraid of each other and that they don’t stereotype or sort each other into “us versus them” categories.

Donald Trump was incredibly good at that. Unfortunately, his opposition doesn’t know how to tell stories as well. So, power hungry individuals keep playing on the fears of difference and trying to steer the people behind them against the others. One common way to deal with these populist provocateurs is irony and satire, but I believe that getting people to tell each other their stories and listen to each other is far more powerful than ironic speech or comedians making fun of politicians.

What would you like to pass on as a message to the Mensans reading this?

We have all succeeded in scoring high on our tests for intellectual ability. We need to score just as high on our EQ as on our IQ. It can be fun to be with a lot of other smart people, but how do you take that into your life in such a way that it’s enriching for the people around you as well as for yourself? I am happy to be in touch again!

Links to web:

Diversophy: diversophy.com

Diversity: diversity.com

SIETAR: sietareu.org

Workforce 2000: eric.ed.gov/?id=ED290887

NAFTA: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/North_American_Free_Trade_Agreement