mensanthropist [ men-san-thruh-pist ] noun

a person, who actively participates in fulfilling one of Mensa’s objectives by fostering and utilizing intelligence for the benefit of humanity

Unfortunately, I did not manage to personally interview the mensanthropist this article is about. He died less than a year ago. But his legacy will remain with us for a long time, and his life was such an accurate embodiment of the above definition that I simply couldn’t leave him out of my series.

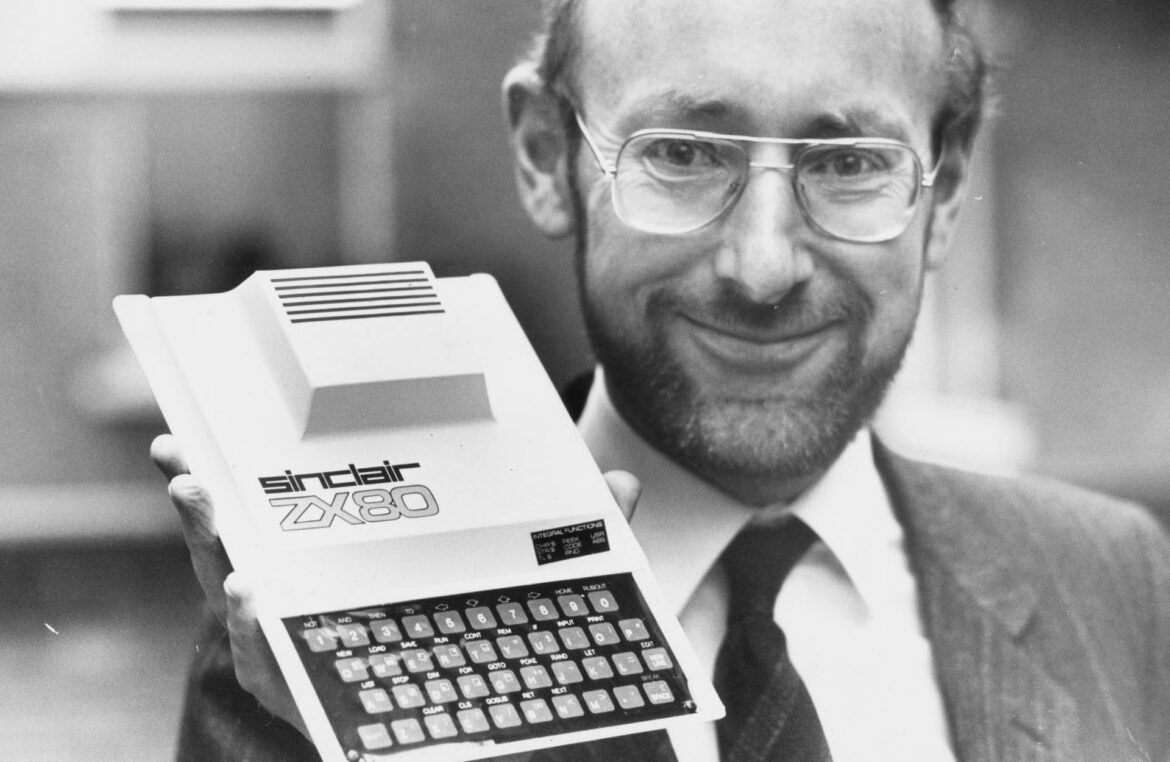

Perhaps not many people outside the UK know that he was chairman of British Mensa for 17 years, specifically from 1980-1997. But you’d be hard pressed to find a man in the whole of Europe who grew up in the 1980s and doesn’t connect the name Sinclair with a small personal computer that used a cassette recorder as a recording medium and a TV set as a monitor. It was his ZX80 that made personal computers affordable to ordinary British families on average incomes in the 1980s. Its successors, the ZX81 and ZX Spectrum, then quickly spread the phenomenon not just across Europe but around the world, partially thanks to local companies starting to produce clones in large numbers, such as the Slovakian Didaktik Gama.

But the small computer was not the first of his creations to change the world. He began to have a significant impact on the lives of his and following generations of people long before that…

Passion for miniaturization

Sir Clive Sinclair was born on 30 July 1940 and a war intervened in his life virtually immediately after his birth. He and his mother escaped from it to his aunt in Devon. It turned out as lucky, because soon their home was hit by German bombing. It’s hard to find out for sure where Clive Sinclair was born. Some sources say Ealing, others Richmond. But Ealing, which is mentioned in one of the published interviews, seems more likely. Richmond is probably mentioned as the place of birth because Clive lived there after the war and went to school there, specifically Tiffin Boys‘ School.

As a twentieth-century inventor, Clive Sinclair could not have timed his arrival in the world better. His greatest passion was miniaturization. He was convinced that for technological advances to benefit the masses, they had to be small and cheap. The two inventions that helped miniaturization perhaps the most were the transistor and the integrated circuit. The first working germanium transistor was made by John Bardeen and Walter Brattain at AT&T’s Bell Laboratories in December 1947, when little Clive was seven years old. Yet just 12 years later, Sinclair published his first two books, one on transistor receivers, the other on stereo audio systems, including schematics and instructions for building the necessary electronic circuits.

At school, Clive excelled in maths, but he was not interested in sport at all and most other subjects were not fun. As a child, he much preferred to spend his free time with adults who could teach him something, rather than with his peers. He reportedly started secondary school at the age of 10, a year earlier than usual in the British education system. By the age of 12, Clive had built a single-seater submarine from a petrol tank. Due to his father’s financial difficulties, he had to change secondary school several times, so he took his general (O-level) exams at Highgate and his specialist exams in physics, mathematics and applied mathematics at St George’s College, Weybridge.

At seventeen, he decided not to continue his studies at college. He rather wanted to go into business and start implementing his ideas. However, he lacked funding, so he first joined Practical Wireless magazine as an assistant editor, where he had been contributing technical articles for some time. He also earned money by mowing grass and washing dishes in a café. A year later, Jack Kilby demonstrated the world’s first working integrated circuit…

Radios and calculators

Clive started his business in 1961 by founding Sinclair Radionics. By then, TTL integrated circuits were a reality already and subsequently dominated the electronic world in the 1970s and 1980s.

Sinclair initially sold transistor radio kits, which he made in the evenings at home and mailed to customers. The company’s first products were mainly radio receivers and hi-fi amplifiers, mostly offered in the form of self-assembly parts kits. Although Sinclair later began selling his products assembled, most were still available as kits at a lower price as well.

All of Sinclair’s products at the time had one thing in common. They were smaller and cheaper than what the competition was offering. In 1964, he launched the world’s smallest radio named Micro-6 which fit in a matchbox. With the advent of integrated circuits, its miniaturization began to gain momentum. In 1966, he created the first pocket TV. But this invention had to wait ten years for commercial production due to the high manufacturing cost. In 1972, he launched the Sinclair Executive pocket calculator, which was less than 1 cm thin while the thinnest competing product (the Japanese Busicom LE-120A „HANDY“ calculator) was more than twice (23 millimetres) as thick.

Pocket calculators were Sinclair’s main source of income in the 1970s. Yet he managed to drive the company nearly to bankruptcy in 1975 with another product, the Black Watch, a digital timepiece. This was because it was unreliable, inaccurate, had to be pressed to display the time, and lasted only ten days on the battery instead of the advertised one year. In addition, the company was not keeping up with the orders it received. Not that it didn’t remind me of my Apple Watch…

But more than its failure, the watch was interesting for the way it spoke about Clive’s priorities and approach to invention. Financial gain was clearly never his priority. His main goal was to move people into the future and he saw education as one of his main means. Although he did not seek it in the traditional school, he himself was eager for new knowledge and wanted to offer the same to others. That’s why he offered most of his products in the form of a kit, and the digital wristwatch was no exception. Its failure stemmed, among other things, from the fact that Sinclair probably did not fully address the fact that the requirements for successful assembly of such a kit were already too high.

ZX comes to the scene

The same goal motivated Sinclair to buy out and start a second company, which gradually changed its name from Ablesdeal to Westminster Mail Order, Sinclair Instrument, Science of Cambridge, Sinclair Computers (from 1979) to Sinclair Research. It was this company that came up with the Sinclair ZX80 computer (named after the year it was introduced) in 1980. In fact, a year earlier, after the launch of the £700 Commodore PET, The Financial Times had forecast that the price of similar personal computers could fall to £100 in five years, which at the time was about a fifth of the average monthly salary in Britain. Sinclar decided to accelerate development and offered its computer fully functional for £99.95 in 1980, and even £20 cheaper as a kit again.

He hoped that young people would learn to program on the computer. That’s why it also came with the BASIC programming language included. It was a bit of a disappointment to Clive that „Sinclairs“ then spread to homes all over the world mainly through games and only a fraction of users learned to program on them.

The ZX80, ZX81 and ZX Spectrum computers were Sinclair’s greatest commercial success, earning him millions of pounds, a knighthood, honorary doctorates from the University of Bath, the University of Warwick and the University of Heriot-Watt, an honorary fellowship of Imperial College and an honorary fellowship of the Manchester Institute of Science and Technology. In 1999, he also received the Computer Entrepreneur Award from the IEEE Computer Society „for his spirit of innovation and entrepreneurship, which has been a source of inspiration and guidance to the computer industry worldwide.“ Bill Gates, Paul Allen, Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak had received the same award a year earlier, and Michael Dell a year later.

Unfortunately, as with Sinclair Radionics, the success didn’t last long. The next product was to be Sinclair QL, aimed at freelancers and small businesses. Launching on January 12, 1984, 12 days before Apple introduced the Macintosh, Sinclair hit the right timing, but didn’t manage to get the computer into a fully usable state. By the time he could fix all the flaws, it was too late to save the product. In 1985, he tried to raise money to restructure the company, but failed, and eventually sold all the rights to the computer product line to Amstrad a year later. He retained Sinclair Research for research projects and gradually downsized the company until he was left alone in 1997.

Electric cars and bikes

Another area that Clive Sinclair began to pursue alongside computers was transportation equipment. In 1983 he founded Sinclair Vehicles, which was joined as a director by Barrie Wills, formerly of the DeLorean Motor Company. Its first and only product was the Sinclair C5 single-seater electric car, launched in 1985. However, it did not get a positive response from the public and media and the company closed later that year.

But this, along with other projects in the field of transportation that later reappeared under the Sinclair Research banner, such as the A-Bike folding bicycle, the Zike lightweight electric bicycle, the ZETA universal electric bicycle drive, the ZA20 wheelchair power unit, the X-1 two-wheeled pedal electric car and the electric version of the A-Bike, subtly suggest something of what kind of inventor Clive Sinclair was. That he wasn’t so much concerned about commercial success as about the real benefit to humanity.

The A-Bike Electric project website (http://a-bike.co.uk), when it still existed, presented Sinclair’s quote: „The idea is if you had a bicycle which was seriously lighter and more compact than anything existing at the moment, it would change the way in which people saw bikes.“ His C5 e-bike may not have been a success in its day, but it may just have been ahead of its time.

Don’t give up

In an interview with Richard Sharp in February 2019, when asked what advice he would give to young people looking to enter the world of IT or start a business, he replied, „Don’t give up. Stick at it.“ In the same interview, he said: „What I’ve done well, if I may say so, is to see the future. Forty years ago I gave a talk to Joint Committee of Congress on the future. And I projected a lot of thins then which came to pass, including driverless cars. I remember saying, you enjoy driving, do it while you can because one day you won’t be allowed to.“

He often claimed that there was no point in asking people if they would want his invention because they couldn’t imagine it. When he got an idea of what he wanted certain thing to look like in the future, he didn’t let anyone talk him out of it and just went ahead and tried it, regardless of whether it took off. Sometimes he just came up with it too early. But in doing so, he had a knack for pulling even more out of the available technologies than they were built for. For example, he extended the battery life of his pocket calculator, the Executive, before LCD displays later achieved that. He simply noticed that the LEDs would stay lit for a while after the electric current stopped flowing through them – so instead of keeping the calculator’s display on all the time, he made it blink.

According to his daughter Belinda, he was a wonderful person and was interested in everything. He wanted to make things small and cheap so that people could easily access them. In 1985, in a television interview, in response to a question about an upcoming portable computer model, he said he was convinced that one day all devices would be portable.

Poker, poetry and the universe

In contrast to all this, Sinclair did not use his own inventions. Instead of a calculator, he carried a slide rule everywhere, and in all his interviews he said he didn’t use a computer or the internet. He was even worried that artificial intelligence beyond the human one would threaten our survival. According to Janet Goodenough, the Mensan I had the opportunity to talk to about Clive Sinclair, he never read or sent a single email. „It was basic old fashioned phone calls and snail mail on ordinary paper with a pen. I’ve got cards he sent. We talked a lot via phone.“

Janet met Sir Clive at a „Midsummer Madness“ party he was hosting for Mensans at his penthouse near Kings Cross, and they became close platonic friends for the rest of Clive’s life. Clive is said to have found the publicity hard to take, especially after his divorce from his first wife and the C5 electric car debacle, after which the press picked on him a lot in a negative way.

In addition to the inventions he lived for, Clive Sinclair was very fond of poetry, literature and poker. „If he had a subject he enjoyed, he researched it thoroughly. So he had a very strong grounding, comprehensively across literature. He was a polymath, but towards the scientific side more than the literary artistic side.“

„He was a really good poker player. In his latter years, he moved from Kings Cross to a place that was being renovated up into apartments, having been a big Lloyds Bank on Trafalgar Square. He bought two apartments there and had them fitted out to his requirements, one for himself, and another for his mother, who he cared for in her dying days. When her time came, it was leased by an American who also loved playing poker. He and Clive became friends and they’d just play poker together as a hobby. And that gave him pleasure in his final years. Poker, for Clive, was nothing to do with gambling. It was an intellectual pursuit, testing his brain and keeping it in mathematical trim. He could remember card packs and calculate odds with acute precision. He played internationally in Las Vegas. At a national tournament, run by Victoria Coren Mitchell in Cardiff, he won €20.000 and insisted on having it paid in cash. He took the suitcase of money back to London on the train. Typical Clive!“

But he was also interested in space research. „He really wanted us to move off the planet and have a Planet B. He was full of visions. He at one point imagined us all driving around in airborne cars to reduce traffic. He was really worried about the traffic situation, having he lived in Cambridge for a long time. Cambridge is a very ancient city, not made for cars. It grew up as a village and an academic center and was made for horses rather than anything modern and electronic. You can put the development of the Sinclair C5 down to a very practical solution to gridlock in Cambridge. If everyone was riding around in little C fives, there would be no gridlock. And then the idea of the flying car. It just made sense again. Totally practical. If only it were possible. He was just driven by a vision.“

Part of Mensa

Clive Sinclair became a member of Mensa in 1959 with an IQ of 159. Although in Mensa circles the specific measured IQ of members is not usually mentioned, and is even considered rude, this figure is mentioned by many sources, perhaps because of how nice it looks next to the year it was measured. He took the helm of British Mensa as its chairman in 1980, when it was experiencing an unprecedented rise in reputation thanks to people like Madsen Pirie, Brian J Ford, Victor Serebriakoff and David Schulman. Under Clive’s leadership, the success then continued, the membership base grew to nearly 40,000 members and the Mensa name got literally domesticated in the UK.

Even after he was knighted, Sir Clive insisted that he should still be addressed by his first name, Clive, by other members. To Czechs who, after 40 years of totalitarianism, don’t much care for titles of nobility, this may not seem that significant, but in Britain it meant that he put the Mensans on the same level as immediate family.

Brian Page, the current editor-in-chief of the British Mensa magazine, remembers Clive as very shy and quiet. „But he loved Mensa gatherings immensely and felt very much at home in Mensa company. He particularly liked the wilder/more eccentric members who he said made him laugh out loud. He would quite often be in boisterous company where much drink was taken but he rarely drank much himself. I do remember once chairing a ‚question and answer‘ session with members. Clive and I were on the stage with a bottle of whisky between us. It wasn’t touched during the meeting – but was soon polished off afterwards.

Clive had no time for the more pompous aspects of the society and very much believed it was a social club where people who didn’t always fit in felt at home. He was also famously quoted as saying that Mensa was a place where intelligent people went to get laid (have sex). He didn’t do many interviews but we did a couple together over the years and he was always hugely self-effacing and modest. My favourite answer to an interview question… I asked what he would most liked to have invented – to which he replied the ballpoint pen…“

Sylvia Herbert, a former councillor of both British Mensa and Mensa International, met Clive Sinclair at a Mensa weekend in 1994: „I hadn’t been very active until attending this weekend. I found a few members happily chatting in the reception/bar area. They made room for me and I sat down and was happily chatting to the man next to me for about half an hour before I discovered it was Sir Clive! There were only about 45 members at that weekend but it actually ‚sold‘ me on Mensa.“

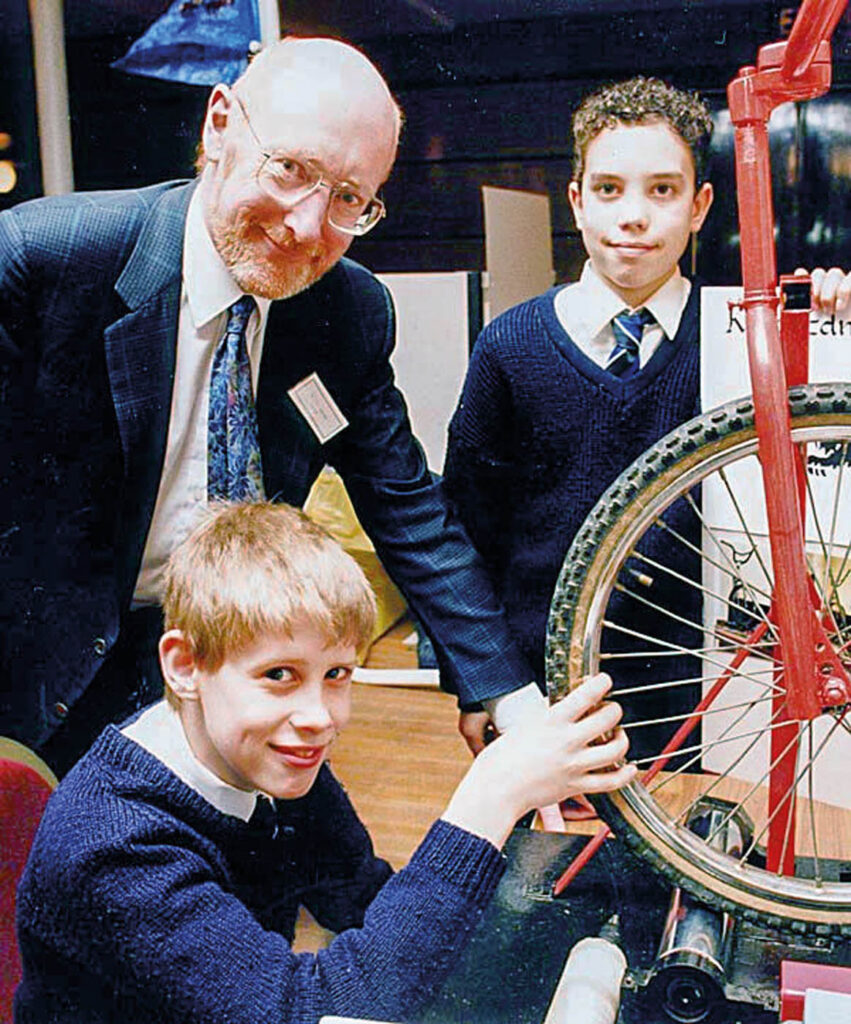

A few years later, at a Mensa gathering in the seaside resort of Blackpool, she got to know another side of Clive’s personality: „He searched the room for people he knew and came over to join us. I guess my son, who works in IT, was impressed! I think it was because Sir Clive was basically a shy person and I was someone he recognised best. During the evening, the entertainment included recitations by members. After one had recited three stories at length, Sir Clive muttered ‚Not another one! When is he going to finish!!?‘ It was clearly not his favourite style of entertainment!“

But shyness has sometimes been replaced by eccentricity: „I recall two PR events with Sir Clive that are somewhat connected. A photo opportunity featuring Sir Clive was organised to take place in the London Science Museum and press releases went out to the major newspapers. On the night, we arrived at a side entrance and had to walk through the lower galleries to get to the top floor where the photo opportunity was to be held. On the way through, Sir Clive kept darting off to look in cabinets, pointing to watches, calculators and small computers exclaiming excitedly ‚That’s one of mine!‘ ‚That’s another of mine‘. The press didn’t turn out, apart from one national, so he was disappointed and decided Mensa should look less stuffy. So a trip was organised to the London club Stringfellows for dinner. After a great dinner there one of the hostesses climbed on the table and tried to get a photo of him looking up her legs. I knew those headlines wouldn’t be the best, but he actually wouldn’t have minded…“

Clive’s legacy

Sir Clive Sinclair was not only very clever but also very generous. He gave Christmas presents to all employees, regardless of their position in the company. He threw big parties. He gave the man who mowed his lawn a ZX Spectrum for his kids. He made money on some of his creations, lost money on others, but he gave us all something. Some of his inventions affect our lives to this day, other ideas were so ahead of their time that they have yet to come in some form. Pocket TVs and calculators are now part of a smart phone, digital watches are small computers, electric cars are gradually replacing petrol ones, automatic driving is already being tested in real traffic, we are trying to solve the traffic situation in cities with shared cars, bikes and scooters, children are starting to learn programming in primary schools.

Do you, like Sir Clive, have a vision of a better future? An idea that would improve things? Then stick at it. Even if you don’t get it right the first time, your efforts may pay off one day.