mensanthropist [ men-san-thruh-pist ] noun

a person, who actively participates in fulfilling one of Mensa’s objectives by fostering and utilizing intelligence for the benefit of humanity

Twenty-four is a number with a special meaning for me, so I decided to dedicate the twenty-fourth installment of this series to the man who is actually indirectly responsible for its very existence. Victor Serebriakoff is known as the man who saved Mensa from extinction, built it into what we know it as today, and pushed today’s first goal into its constitution – the one that inspired me for the name Mensanthropist.

Where did Victor Serebriakoff come from?

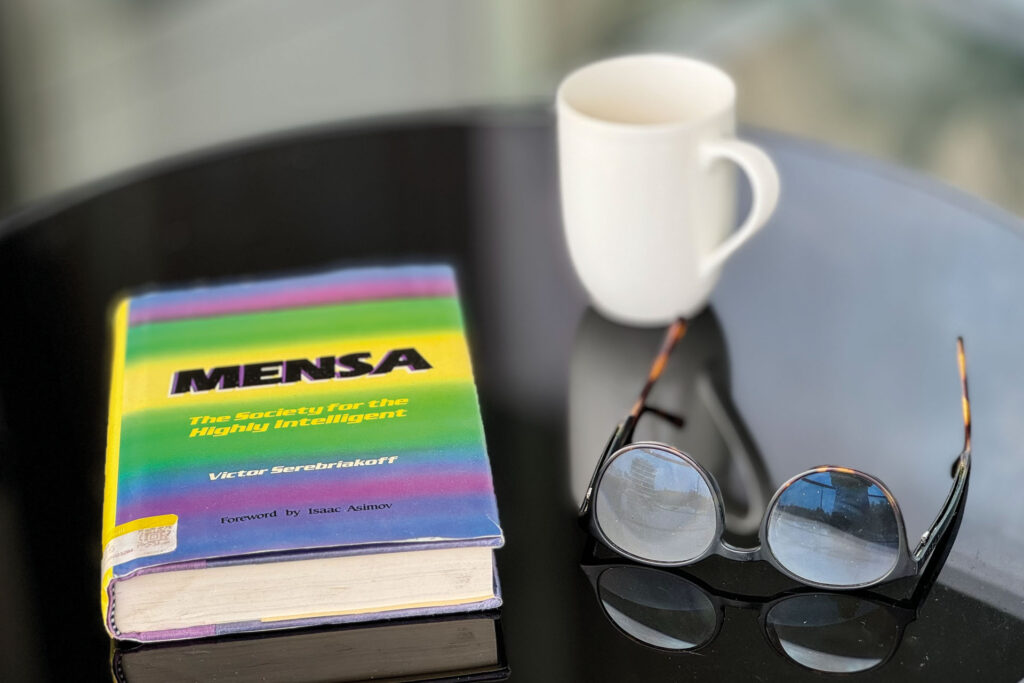

There is quite a bit of information available about most of what Serebriakoff did in and for Mensa. Partly because he wrote two books about it himself. The first one was published in January 1966. The second appeared initially in January 1985 in the UK with a foreword by Sir Clive Sinclair, and then a year later in the US with a foreword by Isaac Asimov.

Information about Victor’s life outside Mensa has been harder to come by, so I’m glad I’ve been able to talk or write to a few people who knew him personally. The family history website (serebriakoff.net), written and maintained by Victor’s son Mark, was also a helpful resource to me.

Victor’s father, Vladimir, was the son of a Russian Naval officer who emigrated in 1888. He was born in Geneva, grew up partly in Paris and partly in London, where he married Ethel Graham in 1912. The same year their son Victor was born. Victor had 6 younger siblings, Katherine, Mavis, Dorothy, John, Dora and Barbara.

There are also various rumours and fictions running around from Victor’s childhood. For example, one Korean author says in his book how Victor’s mother took Victor to the doctor because he was stupid and couldn’t do anything, and to prove he wasn’t stupid he completed the Rubik’s cube in a few seconds. In fact, Ernő Rubik did not create his puzzle until 1974, when Victor was 62 years old. Victor was actually considered more of a nerd by his classmates. In an interview with the Chicago Tribune in 1986, he said: “I was chased home from school every day because I was the kid who put his hand up at every question. The teachers liked me all right, but the other kids didn’t.”

From labourer to theatre, from theatre to army

He dropped out of school and started working first as a sales clerk in a timber company. During the depression, he traded manual work for unemployment several times and became interested in politics. He joined the Labour Party and in the factory where he was working he joined a group trying to form a union. He writes he was then cured of his left-wing views for good during the war by the announcement of a pact between the Soviets and the Nazis.

While working as a labourer in a cable factory, he began to come up with ideas on how to do things better, but encountered reluctance from his superiors to change established practices. In his diary, which he kept from December 1935 to May 1936, there is an account of how “foreman gave him a job to cut wedges, and he came back half a day later with it all done. The foreman couldn’t understand how he’d done it so quickly. After revealing he’d found a better way to do the cutting, the response of the foreman was to do it the proper way next time.”

That may be why he got involved in amateur dramatics in his spare time. His creativity just wanted to get out. His involvement started with putting on little shows for the other workers in the factory. Later he joined several theatre groups and even wrote his own plays. He wrote of himself that he “was reading Freud, Jung, and Adler, and made a decision that he did not want to be an introvert anymore,” and that he “changed into one of the world’s most bouncing extroverts.”

When the war started, his work was considered vital, so he was not called up. He said of himself that “he was doing mundane routine work cutting timber that even a retarded monkey would have been bored by.” He was so passionate about the theatre that in 1945 he joined ENSA (Entertainments National Service Association), which organised entertainment for British soldiers. This got him out of the reserved occupation and he was called up for national service on 13 March 1945. It was in the army where he was first subjected to an intelligence test with the surprising discovery that his IQ was above average. He joined the army at the very end of World War II, having his training completed just in time for the victory parade.

After leaving the service in 1947, he was given the choice of a career as an actor, a university degree for ex-soldiers, or a “vaguely managerial position” in a newly established timber company. He chose timber and within a year was managing the company.

Father of two, stepfather of Mensa

Shortly after beginning a successful career as a sawmill manager, Serebriakoff got married, bought a house, and in 1949 his son Mark was born. In the same year, his wife Mary alerted him to a newspaper advertisement promoting a society for highly intelligent people called Mensa. “She was doing that mainly to get him out of the house, to get him out from under her feet,” Mark believes. Victor initially thought it was a scam, but was convinced and replied to the advert with a letter. He writes how it went in his book:

“Roland Berrill’s prompt reply to my letter brought a ‘preliminary’ home IQ Test. If I did well enough on this I was to be summoned for further examination. I did the test and sent it back. Berrill’s autocratic reply firmly announced that I had ‘cleared the bar at the arbitrary height at which we have pegged it, with sufficient daylight to spare, that we can accept you on the preliminary test alone without more ado.’”

It was Berrill who founded Mensa three years earlier, the idea for which was supposedly suggested to him by Dr. Lancelot Lionel Ware on a train one day. He is now officially listed as a co-founder. Berrill wanted to build an elite aristocratic-style organisation with a maximum of 600 members, providing advisory to government officials.

Victor had his first personal encounter with Mensa a year later: “My first really intoxicating injection of the Mensa drug did not occur until many months later after reading the curiously compelling, autocratic instruction in a later edition of the Mensa Quarterly. We were all to sleep under the same roof at the Charing Cross Hotel on the Saturday 4 November 1950. I was summoned to the Presence. Resist I could not.”

This was less than a month after the birth of his daughter Judith. Mary’s idea to get Victor out of the house started to work. His first impression of the encounter was not unlike what many Mensans had experienced:

“For the first time in my life I was able to talk in a completely uninhibited way: argument, discussion, dispute, contestation, all going forward in a suave and civilised way.”

Sadly, Mary was diagnosed with cancer shortly afterwards, from which she died in 1952. And while Mary was dying, Mensa membership went from ten to five. Roland Berrill, as founder, could not agree with the recruited members on where the organization should go. The hospital recommended the newly widowed Victor to a “lady almoner” for help. This turned out to be Winifred Rouse, whom, coincidentally, Victor already knew from Mensa meetings. In the aristocratic version of the organization, she even held the position of “Corps d’Esprit” at that time, a kind of formal queen, one of Berrill’s ideas… Victor and Win became close and soon married.

Mark and Judith lived with their grandmother, Mary’s mother, from the time of Mary’s death until 1957, and only rarely saw their father. “I think we saw him maybe once or twice a year, no more than that,” Mark recalls. This gave Victor plenty of time to devote to Mensa in addition to his work. He couldn’t save Mary, so he saved Mensa.

Ray Ward told me: “He’s credited with saving Mensa when it effectively fell to about four members… What the actual paid up membership of Mensa was at that time, the early 1950s, nobody knows because the membership records are lost. [It was 120 according to Victor’s book.] But the only regular Mensa event was a dinner at a restaurant in Soho attended by the secretary Joe Wilson, his twin brother George and Victor and his wife Win. And for several consecutive months, they were the only attenders. Joe Wilson said, this isn’t really an organization or a club or a society. We’re just four friends who enjoy dining together. And Victor said, that’s a pity. He officially became joint secretary with Joe Wilson, but in fact, almost from that moment on, Joe Wilson dropped out, and Victor was left running Mensa, which he did with great enthusiasm and enormous energy.”

Perhaps because Mark was only 3 when he and his sister moved to live with their grandparents, he didn’t miss his parents: “It felt normal to a child. I just didn’t understand the significance of what had happened. Grandma and granddad fulfilled the role of parents.” But Victor didn’t slack off, even when he and Win took the children in five years later.

“Disciplining of me and my sister was mainly done by Win. I mean, Mensa was like an older brother taking more time away from me and my sister. Mensa was something that really occupied him quite a lot. He was quite involved in business, then he would come home and do Mensa stuff, and then he was writing books. I just accepted things as normal because I had no other comparison to it,” Mark continues.

But that doesn’t mean that Victor would shut himself up at home and the children wouldn’t see him: “Great thing that we benefited from as children was that he had all sorts of people coming to dinner. There would be quite intense conversations at the dinner table, when he invited guests like Clive Sinclair or Christopher Frost. That was quite beneficial to see all these intelligent people and hear their conversations, not everyone gets the privilege to hear that sort of thing.”

Building Mensa

When Serebriakoff took over the running of Mensa from Wilson, his main goal, which remains a measure of Mensa’s success to this day, was to grow the membership base. He did not share Berrill’s idea that it should be restricted by the number 600, nor that it should remain just a local British organisation. As Therese Moodie-Bloom writes in the September 2013 Mensa World Journal, “Victor Serebriakoff used to speak of his golden vision of Mensa as a global village.”

One of the obstacles to Mensa’s growth has been a disagreement among its members. According to Mark, “He knew that you get two Mensa members together and you’ve got three opinions.” Victor himself writes in his book about Mensa: “Mensa is the living proof that, contrary to the adage, great minds (or at any rate bright minds), think unlike. The result of applying intelligence to an unsettled or controversial problem is the reverse. There are more and not fewer different opinions, less not more agreement.”

Victor solved it with the rule that Mensa as such has no opinion: “I dropped all mention of the possibility of being a Think Tank to advise the authorities and, remembering Berrill’s mistake in muddling his own and Mensa opinion in public, emphasised strongly that Mensa was impartial, uncommitted, and disinterested. Mensa was to be an agora, a forum for the exploration of opinions, not a pressure group with its own opinions or collective aims. This has remained our hidden strength through the years.”

He also came up with a new way of promotion. Instead of promoting Mensa as such, he published advertisements in more serious newspapers, offering people the opportunity to test their intelligence, without specifying why. “I remembered my motivation in my own application and guessed that people would be curious to know their IQ.” Later he became even more successful in publishing simplified IQ tests or various puzzles.

Back home in London, he began to organise discussion evenings known as “Think-Ins”, which were very popular. The format of the meetings was that “a distinguished speaker makes a speech on some speculative or controversial topic and this is followed by an hour and a half of discussion to which everyone is encouraged to contribute. The best of these are marvellous with lots of wit and clever joking, as well as serious, thoughtful talk. Even the worst are not bad.”

At the 1956 annual meeting, democracy was established and Victor was elected the first president. In the 1960s, Mensa International was officially founded and Victor, on his travels around the world, began to promote the establishment of local national Mensas. One of the first was American Mensa, where he completed several series of interviews for newspapers and television stations.

In 1967, in Switzerland, Victor met a tiny little priest, “one of the two or three members Mensa International had in Sicily at that time.” This personal encounter was to prove influential for both Victor and Mensa. Fabio Marcedone, who met the priest in person many times, writes: “Don Calogero told Mr. Serebriakoff that Mensa should not only collect and connect intelligent members, but should also foster giftedness for the general benefit of humanity. Why couldn’t Mensa raise its own pupils? As a demonstration of what could be done, he built and ran a special ‘Village’ for gifted children.”

Victor was so impressed by the idea that he had Don Calogero personally present it at the next IGC (International General Committee) meeting in Lugano, and it was accepted by a large majority as the third, now first, aim of Mensa. Until then, Mensa’s first constitution of 1964 stated only two purposes: research on intelligence in psychology and in social sciences, and the opportunity for social contacts between its members. This new aim began a new chapter for Mensa, with a strong focus on identifying intelligence soon enough to foster it as much as possible.

For the rest of his life, Victor was totally committed to Mensa and its mission. He never gave up, even when people were throwing a wrench into his works. The following memoir by Isaac Asimov is a good example of Victor’s tenacity:

“As time passed, I moved to New York in 1970, and in 1972, Victor Serebriakoff visited New York and demanded to meet me for some nefarious reason of his own. (He’s never had an un-nefarious reason in his life.) I was not proof against the imperious summons. There I was staring at this five-foot-five fellow with a seven-foot-seven charisma. ‘Why,’ he demanded, ‘have you allowed your Mensa membership to lapse?’ I tried to explain. He dismissed the explanation with an impatient “Tchah! (which may be Russian for ‘In your hat,’ but I’m not sure). Then he said, ‘Just renew your membership.’ I demurred (more Mensa talk).

‘You might as well,’ he said, with a Serebriakoffian snarl, because if you don’t, I’ll pay your dues for you and we’ll list you as a member, anyway.’”

Timber innovations

In the timber industry, Victor soon became known as an innovator in woodworking technology. For example, he invented a machine for automatically grading timber according to strength. Mark writes on the family website: “His principal development was the automatic grading of timber for strength, which allowed for the more efficient structural use of timber. Stress grading machines were sold world wide. Towards the end of his business life he was working on a visual timber grader. He also developed methods of finger jointing structural timber, and a saw plane, a circular saw blade that left a smooth planed surface while cutting timber. In the 1960s he led a British delegation to Russia where a conference was being held to discuss the process of metrication of the Timber trade.”

Victor has written two books about the timber industry. The first, British Sawmilling Practice, was published in 1963, and the second, promoting the introduction of the metric system, was published in 1970. He published the books under the name Victor Serry because he feared that in the post-war business and professional world, his ‘German-sounding’ surname might undermine the trust of readers.

Victor as author

In addition to woodworking, Victor has written many other books, including two on Mensa, four on intelligence and the workings of the human brain, he has not omitted even poetry. He quite regularly published also IQ tests for self-testing one’s own intelligence or the intelligence of children, and various puzzles and logic problems.

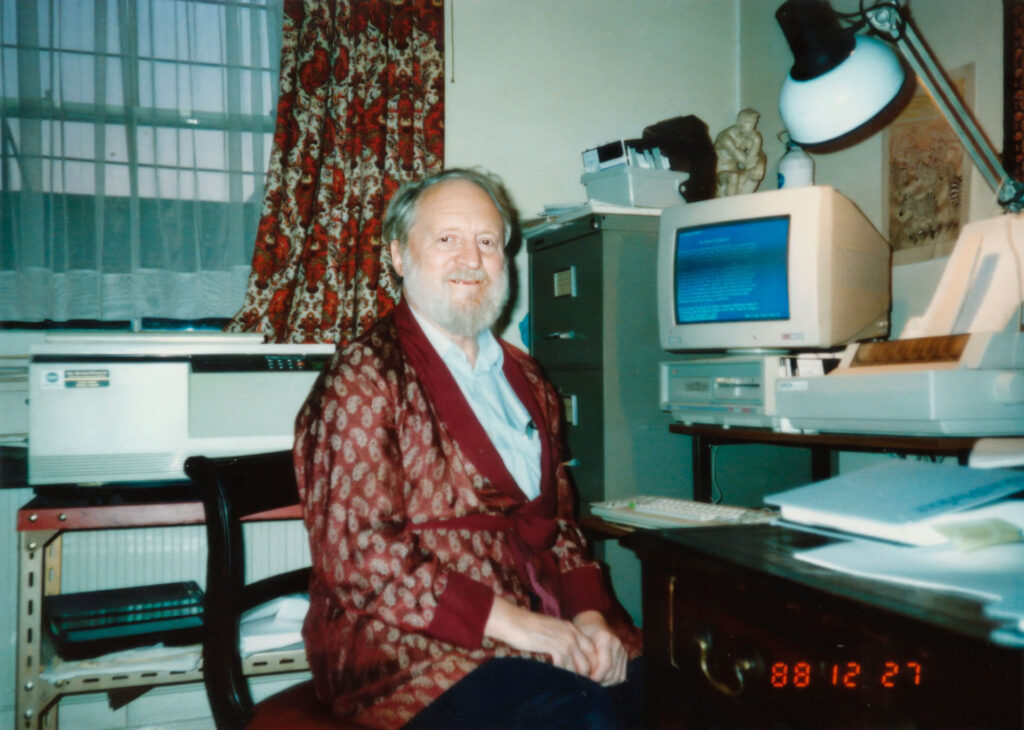

He didn’t write his books by hand or on a typewriter. “He was dictating them to a micro tape recorder, and they were written up by other people. I remember there was one young lady who did a lot of his typing at one point, while she was waiting to go to university. She was doing it in her summer break. But he would pay professional typists as well,” Mark recalls. “When personal computers became more usable he did do a lot of typing, but he also experimented with some of the early voice dictation systems.”

In addition to having a lot to write about, Victor had tremendous powers of expression. When I started reading his book “Mensa: The Society for the Highly Intelligent”, I was both amazed and embarrassed by his vocabulary and unusual turns of phrase. At first, it was a chore to read, but as I started to get into it, I enjoyed it more and more and even something as seemingly boring as the history of a non-profit organization began to be devoured as a suspenseful story.

A South African author reviewing another of his books, Russell Swanborough, had a similar feeling: “The late sci-fi author Isaac Asimov once described Victor Serebriakoff as having a ‘monstrous intelligence’. This does not mean that the reader needs the same, although the English does require a little getting used to. The author can cram more meaning into one sentence than most writers can get into a paragraph.”

Ray Ward demonstrates the depth of Victor’s language knowledge and his appreciation for a good discussion: “He regretted the way in which terms like elite and eugenics have become dirty words. I remember he used to say that, if Mensa was accused of being elitist, he’d say, thank you for the compliment. Then he’d say, do you know the definition of elite from the Oxford English Dictionary? The choice part or flower of society, or of any body or group of persons. As he said, whenever anybody says eugenics, sooner or later someone will say Hitler and all hope of rational discussion goes straight out the window.”

Mark recalls that “the work about which he felt the greatest sense of achievement is his book called ‘Brain’. In this book he sets out a theory of how the brain operates, using a poly hierarchical system of nodes that learn patterns by adjusting their sensitivity to varying input patterns. The book sets out how the poly hierarchical system could be used in organisations, where the nodes are people or units. I have been told that the ideas contained in the book were ahead of their time and that many of the points made in the book are being accepted by people working in the field now.”

The aforementioned South African reader rates the book as “a 5 star read for everyone seriously interested in the subject of information and how the brain (any brain) processes it. I have read this book twice, not because I didn’t get much out of it the first time but because I couldn’t believe how much more I could get out of it the second time. I need to read it a third time…”

Victor finished a revision of his book Brain just before his death.

But Victor didn’t create just books. In his book about Mensa, he writes: “With the help of my family and the permission of my friend, the author Ray Cattell, I wrote a program that would put a candidate through the Cattell IIA test, supervise it in a standard way and mark the test with due age allowance.”

Chris Leek also revealed to me that “in 1987 he invented a new board game called Cashword, which was a cross between Monopoly and Scrabble.”

Victor as a person

Everyone I have spoken to or who wrote about Victor describes him as someone worth spending time with. So his plan to become an extrovert seems to have worked.

Ray Ward describes him as “quite short, but one of those bubbling characters who tend to stand out in any group. But he didn’t dominate it anyway. He was always anxious that everyone who wished to speak should be free to do so. He was sometimes criticized, sometimes quite offensively, but he always remained calm and polite.”

Chris Leek said about him: “Victor was very bright. He was very forceful. He had a lot of ideas, and he would try and make them come real. He was fairly short, bearded, but came over as very impressive and interested in a lot of different topics.”

He was said to be a great storyteller and had a great sense of humor. He often made fun of himself. Later in life, for example, he liked to tell a story about how “he was going to take his car in for a repair one day. They said come back in half an hour. So he decided to take his car to a car wash before taking it back to the garage. As he was entering the car wash, he suddenly realized that the reason he was going into the garage was because the side window was stuck down and he couldn’t get it rolled up.”

To my question, whether his father ever got angry, Mark answered: “Win and Victor were both strong characters and they would have rows and they would be quite fierce. But he was a much more of a person who would have a row and then get over it and be back to normal. But I can’t say that I ever saw him angry outside the house.”

Victor Serebriakoff died after a ten-year fight against prostate cancer on Saturday, January 1, 2000. “I can’t help but feel that one of the reasons was that he decided that was a target to make it to the turn of the century.” Chris said.